路易斯·亨利·摩尔根《美洲原住民的房屋和家庭生活》(二)

字号:T|T

2024-08-27 09:00 来源:建筑遗产学刊

《美洲原住民的房屋和家庭生活》

路易斯·亨利·摩尔根

路易斯·亨利·摩尔根

The Yucatan and Central American Indians were, in their architecture, in advance of the remaining aborigines of North America. Next to them, probably, were the Aztecs, and some few tribes southward. Holding the third position, though not far behind, were the Village Indians of New Mexico. All alike they depended upon horticulture for subsistence, and cultivated by irrigation; cotton being superadded to the maize, beans, squashes, and tobacco, cultivated by the northern tribes. Their houses, with those previously described, represent together an original indigenous architecture, which, with its diversities, sprang out of their necessities. Its fundamental communal type, I repeat, is found not less clearly in the houses about to be described, and in the so-called palace at Palenque, than in the long-house of the Iroquois. An examination of the plan of the structures in Mexico, New Mexico, and Central America will tend to establish the truth of this proposition.

图 14.1 中的祖尼是目前新墨西哥州最大的有人居住的普韦布洛。这里曾经可能有五千名居民,但在 1851 年,人数减少到一千五百人。村子由几座建筑组成,大多数房屋都是经由屋顶平台相互连结的。这些建筑由土坯砖、嵌在土坯灰浆中的石头和灰泥砌成。

In the summer of 1879, Mr. James Stevenson, in charge of the field parties under Major Powell, made an extended visit to Zuñi and the neighboring pueblos, for the purpose of making collections of their implements, utensils, etc., during which time the photographs from which the accompanying illustrations of the pueblos were made. His wife accompanied him, and she has furnished us the following description of that pueblo:

1879 年夏天,詹姆斯-史蒂文森先生率领鲍威尔少校手下的野外考察队,对祖尼人和附近的普韦布洛进行了一次长时间的考察,目的是收集他们的工具、器皿等。他的妻子随行,她为我们提供了以下关于该普韦布洛的描述:

"Zuñi is situated in Western New Mexico, being built upon a knoll covering about fifteen acres, and some forty feet above the right bank of the river of the same name."

"祖尼位于新墨西哥州西部,建在一个占地约 15 英亩的山丘上,高出祖尼河流右岸约 40 英尺。"

"Their extreme exclusiveness has preserved to the Zuñians their strong individuality, and kept their language pure. According to Major Powell’s classification, their speech forms one of four linguistic stocks to which may be traced all the pueblo dialects of the southwest. In all the large area which was once thickly dotted with settlements, only thirty-one remain, and these are scattered hundreds of miles apart from Taos in Northern New Mexico, to Isleta, in Western Texas. Among these remnants of great native tribes, the Zuñians may claim perhaps the highest position, whether we regard simply their agricultural and pastoral pursuits, or consider their whole social and political organization."

"他们的极端排他性为祖尼人保留了强烈的个性,并使他们的语言保持纯正。根据鲍威尔少校的分类,他们的语言是四种语言之一,西南部的所有普韦布洛方言都可以追溯到这四种语言。从新墨西哥州北部的陶斯(Taos)到德克萨斯州西部的伊斯莱塔(Isleta),在曾经遍布居民点的大片土地上只剩下 31 个居民点,这些居民点相距数百英里。在这些伟大的土著部落的残余中,祖尼人也许可以称得上是地位最高的,无论我们是单纯考虑他们的农业和畜牧业,还是考虑他们的整个社会和政治组织。"

"The town of Zuñi is built in the most curious style. It resembles a great beehive, with the houses piled one upon another in a succession of terraces, the roof of one forming the floor or yard of the next above, and so on, until in some cases five tiers of dwellings are successively erected, though no one of them is over two stories high. These structures are of stone and ‘adobe.’ They are clustered around two plazas, or open squares, with several streets and three covered ways through the town."

"祖尼镇的建筑风格非常奇特。它像一个巨大的蜂巢,房屋一个接一个地叠成梯田,一个梯田的屋顶是上一个梯田的地板或院子,依此类推,直到有些地方连续建起了五层住宅,但没有一栋超过两层楼高。这些建筑都是石头和 "土坯 "结构。它们集中在两个广场或露天广场周围,广场上有几条街道和三条暗道穿过城镇。"

"The upper houses of Zuñi are reached by ladders from the outside. The lower tiers have doors on the ground plan, while the entrances to the others are from the terraces. There is a second entrance through hatchways in the roof, and thence by ladders down into the rooms below. In many of the pueblos there are no doors whatever on the ground floor, but the Zuñians assert that their lowermost houses have always been provided with such openings. In times of threatened attack the ladders were either drawn up or their rungs were removed, and the lower doors were securely fastened in some of the many ingenious ways these people have of barring the entrances to their dwellings. The houses have small windows, in which mica was originally used, and is still employed to some extent; but the Zuñians prize glass highly, and secure it, whenever practicable, at almost any cost. A dwelling of average capacity has four or five rooms, though in some there are as many as eight. Some of the larger apartments are paved with flagging, but the floors are usually plastered with clay, like the walls. Both are kept in constant repair by the women, who mix a reddish-brown earth with water to the proper consistency, and then spread it by hand, always laying it on in semicircles. It dries smooth and even, and looks well. In working this plaster the squaw keeps her mouth filled with water, which is applied with all the dexterity with which a Chinese laundry-man sprinkles clothes. The women appear to delight in this work, which they consider their special prerogative, and would feel that their rights were infringed upon were men to do it. In building, the men lay the stone foundations and set in place the huge logs that serve as beams to support the roof, the spaces between these rafters being filled with willow-brush; though some of the wealthier Zuñians use instead shingles made by the carpenters of the village. The women then finish the structure. The ceilings of all the older houses are low; but Zuñi architecture has improved, and the modern style gives plenty of room, with doors through which one may pass without stooping. The inner walls are usually whitened. For this purpose a kind of white clay is dissolved in boiling water and applied by hand. A glove of undressed goat-skin is worn, the hand being dipped in the hot liquid and then passed repeatedly over the wall."

"祖尼镇的上层房屋要从外面登上梯子才能到达。底层的门开在地上,而其他层的入口则在露台上。平台上有天窗似的入口,从那里通过梯子下到下面的房间。许多普韦布洛的底层都没有门,但祖尼人断言,他们最底层的房屋一直都有这样的开口。在受到攻击威胁时,梯子要么被拉起,要么被移开,而下层的门则被牢牢地拴住,这些都是祖尼人用许多巧妙的方法来堵住住所入口的。这些房屋的窗户很小,最初使用云母,现在在一定程度上仍在使用;但祖尼人非常喜欢玻璃,只要有机会,他们几乎不惜一切代价也要设法搞到玻璃。一所中等大小的住宅有四五个房间,有的甚至多达八个。一些较大的居室铺石地板,但地板通常和墙壁一样用粘土抹灰。妇女们将红褐色的泥土加水搅拌成适当的稠度,然后用手涂抹,每次都涂成半圆形。泥土干燥后,显得光滑、平整,看起来很好看。在涂抹石膏的过程中,妇女的嘴里要含着水,就像中国洗衣工洒水一样灵巧。妇女们似乎对这项工作乐此不疲,她们认为这是她们的特权,如果由男人来做,她们会觉得自己的权利受到了侵犯。在建造过程中,男人们铺设石基,安放作为支撑屋顶的横梁的巨大原木,这些椽子之间的空隙用柳树灌木丛填充;不过,一些较富裕的祖尼人则使用村里木匠制作的木瓦。然后由妇女来完成结构。所有老房子的天花板都很低;但祖尼人的建筑风格已经有所改进,现代风格的房屋空间宽敞,门可以让人不弯腰就能通过。内墙通常是刷白的。为此,要将一种白粘土溶解在沸水中,然后用手涂抹。在抹白时他们需要戴上没有鞣制过的山羊皮手套,将手浸入热的溶液中,然后一遍遍在墙上涂抹。"

"In Zuñi, as elsewhere, riches and official position confer importance upon their possessors. The wealthy class live in the lower houses, those of moderate means next above, while the poorer families have to be content with the uppermost stories. Naturally no one will climb into the garret who has the means of securing more convenient apartments, under the huge system of “French flats,” which is the way of living in Zuñi. Still there is little or no social distinction in the rude civilization, the whole population of the town living almost as one family. The Alcalde, or Lieutenant-Governor, furnishes an exception to the general rule, as his official duties require him to occupy the highest house of all, from the top of which he announces each morning to the people the orders of the Governor, and makes such other proclamation as may be required of him."

"和其他地方一样,在祖尼,财富和官职赋予了拥有者重要的地位。富裕阶层住在下层,中等收入的住在上层,而贫困家庭只能住在最上层。当然,在祖尼的庞大的 "法式公寓 "系统下,如果有能力获得更方便的公寓,没有人会爬上阁楼,这也是祖尼的生活方式。尽管如此,在这种粗犷的文明中,几乎没有任何社会区别,全镇居民几乎过着一家人的生活。阿尔卡德(Alcalde),即副总督,是这一普遍规则的例外,因为他的公务要求他居住在最高的房子里,每天早上,他都要在房子顶上向人们宣布总督的命令,并发布其他可能需要他发布的公告。"

"Each family has one room, generally the largest in the house, where they work, eat, and sleep together. In this room the wardrobe of the family hangs upon a log suspended beneath the rafters, only the more valued robes, such as those worn in the dance, being wrapped and carefully stored away in another apartment. Work of all kinds goes on in this large room, including the cookery, which is done in a fire-place on the long side, made by a projection at right angles with the wall, with a mantel-piece on which rests the base of the chimney. Another fire-place in a second room is from six to eight feet in width, and above this is a ledge shaped somewhat like a Chinese awning. A highly-polished slab, fifteen or twenty inches in size, is raised a foot above the hearth. Coals are heaped beneath this slab, and upon it the Waiavi is baked. This delicious kind of bread is made of meal ground finely and spread in a thin batter upon the stone with the naked hand. It is as thin as a wafer, and these crisp, gauzy sheets, when cooked, are piled in layers and then folded or rolled. Light bread, which is made only at feast times, is baked in adobe ovens outside the house. When not in use for this purpose, the ovens make convenient kennels for the dogs and play-houses for the children. Neatness is not one of the characteristics of the Zuñians. In the late autumn and winter months the women do little else than make bread, often in fanciful shapes, for the feasts and dances which continually occur. A sweet drink, not at all intoxicating is made from the sprouted wheat. The men use tobacco, procured from white traders, in the form of cigarettes from corn-husks; but this is a luxury in which the women do not indulge."

"每个家庭都有一个房间,通常是房子里最大的房间,他们在这里一起工作、吃饭和睡觉。在这个房间里,全家人的衣柜都挂在悬挂在椽子下面的木头上,只有比较贵重的长袍,比如跳舞时穿的长袍,才会被包起来,小心地存放在另一个房间里。各种工作都在这个大房间里进行,包括烹饪,烹饪是在长边的壁炉里进行的,壁炉是由一个与墙壁成直角的凸出部分制成的,上面有一个壁炉架,壁炉架上放着烟囱的底座。另一个壁炉位于第二个房间,宽六到八英尺,壁炉上方有一个窗台,形状有点像中国木船上的遮阳篷。炉床上方一英尺处有一块高度抛光的石板,大小为 15 或 20 英寸。在这块石板下面堆放着煤炭,淮阿维(Waiavi)就在上面烘烤。这种美味的饼是用磨得很细的玉米粉做成的,用手在石头上抹上一层薄薄的面糊制成。这种饼像威化饼一样薄,煮熟后,这些薄如蝉翼的脆片会一层层堆起来,然后折叠或卷起来吃。薄饼只在节日期间制作,在屋外的土坯炉中烘烤。不用时,这些烤炉就成了狗窝和孩子们的游戏屋。阻尼人不讲究整洁。在深秋和冬季,妇女们除了制作薄饼外,几乎不做其他事情,她们经常把薄饼做成各种奇特的形状,以供宴会和舞会之用。他们有一种用发芽的小麦制成的甜酒,这种酒不很醉人。男人们使用从白人商人那里买来的烟草,用玉米穗制成香烟;但这是一种奢侈,女人不会沉迷于此。"

"The Pueblo mills are among the most interesting things about the town. These mills, which are fastened to the floor a few feet from the wall, are rectangular in shape, and divided into a number of compartments, each about twenty inches wide and deep, the whole series ranging from five to ten feet in length, according to the number of divisions. The walls are made of sandstone. In. each compartment a flat grinding stone is firmly set, inclining at an angle of forty-five degrees. These slabs are of different degrees of smoothness, graduated successively from coarse to fine. The squaws, who alone work at the mills, kneel before them and bend over them as a laundress does over the wash-tub, holding in their hands long stones of volcanic lava, which they rub up and down the slanting slabs, stopping at intervals to place the grain between the stones. As the grinding proceeds the grist is passed from one compartment to the next until, in passing through the series, it becomes of the desired fineness. This tedious and laborious method has been practiced without improvement from time immemorial, and in some of the arts the Zuñians have actually retrograded."

"普韦布洛的磨是该镇最有趣的事物之一。这些磨坊固定在离墙壁几英尺远的地板上,呈长方形,分成若干个隔间,每个隔间宽约 20 英寸,深约 20 英寸,根据隔间的数量,整个系列的长度从 5 英尺到 10 英尺不等。墙壁由砂岩制成。每个隔间里都牢固地安放着一块平整的磨石,呈 45 度角倾斜。这些石板的光滑度不同,从粗到细依次排列。只有印第安人在磨坊工作,他们跪在磨坊前,弯着腰,就像洗衣妇在洗衣盆前一样,手里拿着长长的火山熔岩石块,在倾斜的石板上上下摩擦,每隔一段距离就停下来把谷物放在石块之间。随着研磨的进行,谷物从一个隔间传递到下一个隔间,直到经过一系列的研磨,谷物变得达到所需的细度。这种繁琐费力的方法从古至今一直沿用至今,没有任何改进,而且祖尼人在某些技艺上实际上已经倒退了"。

图2 阻尼人的一间房

The Moki Pueblos are supposed to be the towns of Tusayan, visited by a detachment of Coronado’s expedition in 1541. Since the acquisition of New Mexico they have been rarely visited, because of their isolation and distance from American settlements.

现在有人认为摩基普韦布洛斯就是 1541 年科罗纳多探险队的一支分队访问过的图萨扬镇。自从新墨西哥州被征服后,由于与世隔绝且远离美国人的定居点,这些地方就很少有人造访了。

The accompanying illustration of Wolpi, Fig. 25, one of these pueblos, is from a photograph taken by Major Powell’s party.

图 25 所附的 Wolpi 插图是鲍威尔少校一行人拍摄的照片,Wolpi 是其中一个部落。

In 1858 Lieut. Joseph C. Ives, in command of the Colorado Exploring Expedition, visited the Moki Pueblos, near the Little Colorado. They are seven in number, situated upon mesa elevations within an extent of ten. miles, difficult of access, and constructed of stone. Mi-shong’-i-ni’-vi, the first one entered, is thus described. After ascending the rugged sides of the mesa by a flight of stone steps, Lieutenant Ives remarks: “We came upon a level summit, and had the walls of the pueblo on one side and an extensive and beautiful view upon the other. Without giving us time to admire the scene, the Indians led us to a ladder planted against the front face of the pueblo. The town is nearly square, and surrounded by a stone wall fifteen feet high, the top of which forms a landing extending around the whole. Flights of stone steps led from the first to a second landing, upon which the doors of the houses open. Mounting the stairway opposite to the ladder, the chief crossed to the nearest door and ushered us into a low apartment, from which two or three others opened towards the interior of the dwelling. Our host courteously asked us to be seated upon some skins spread along the floor against the wall, and presently his wife brought in a vase of water and a tray filled with a singular substance (tortillas), that looked more like a sheet of thin blue wrapping paper than anything else I had ever seen. I learned afterwards that it was made from corn meal, ground very fine, made into a gruel, and poured over a heated stone to be baked. When dry it has a surface slightly polished, like paper. The sheets are folded and rolled together, and form the staple article of food of the Moki Indians. As the dish was intended for our entertainment, and looked clean, we all partook of it. It has a delicate fresh-bread flavor, and was not at all unpalatable, particularly when eaten with salt. * * * The room was fifteen feet by ten; the walls were made of adobes; the partitions of substantial beams; the floors laid with clay. In one corner were a fire-place and chimney. Everything was clean and tidy. Skins, bows and arrows, quivers, antlers, blankets, articles of clothing and ornament were hanging upon the walls or arranged upon the shelves. At the other end was a trough divided into compartments, in each of which was a sloping stone slab, two or three feet square, for grinding corn upon. In a recess of an inner room was piled a goodly store of corn in the ear. * * * Another inner room appeared to be a sleeping apartment, but this being occupied by females we did not enter, though the Indians seemed to be pleased rather than otherwise at the curiosity evinced during the close inspection of their dwelling and furniture. * * * Then we went out upon the landing, and by another flight of steps ascended to the roof, where we beheld a magnificent panorama. * * * We learned that there were seven towns. * * * Each pueblo is built around a rectangular court, in which we suppose are the springs that furnish the supply to the reservoirs. The exterior walls, which are of stone, have no openings, and would have to be scaled or battered down before access could be gained to the interior. The successive stories are set back, one behind the other. The lower rooms are reached through trap-doors from the first landing. The houses are three rooms deep, and open upon the interior court. The arrangement is as strong and compact as could well be devised, but as the court is common, and the landings are separated by no partitions, it involves a certain community of residence."

1858 年,约瑟夫·C·艾夫斯中尉在科罗拉多探险队的指挥下,访问了小科罗拉多附近的摩基普韦布洛斯(Moki Pueblos)。这些部落共有七个,坐落在方圆十英里的山丘上,交通不便,由石头建成。第一个进入的米-肖恩-伊-尼-维是这样描述的。艾夫斯中尉通过一段石阶登上崎岖的台地后,说到:"我们来到了一个平坦的山顶,一边是普韦布洛的城墙,另一边是广阔而美丽的景色。印第安人没有给我们欣赏美景的时间,就把我们带到了靠着普韦洛正面的一个梯子上。这个小镇几乎是正方形的,四周是 15 英尺高的石墙,墙顶形成了一个环绕整个小镇的平台。石阶从第一层通向第二层,房屋的门就开在第二层上。酋长爬上梯子对面的楼梯,走到最近的一扇门前,把我们领进一间低矮的房子,从这间房子里,还有两三间房子向住宅内部敞开。主人彬彬有礼地请我们坐在靠墙铺在地板上的几张皮上,他的妻子很快端来了一个花瓶和一个托盘,里面装满了一种奇怪的东西(玉米饼),看起来更像是一张薄薄的蓝色包装纸,而不是我见过的任何其他东西。后来我才知道,它是用玉米粉磨成的,磨得很细,煮成稀粥,倒在加热的石头上烘烤而成。烘干后,它的表面就像纸一样略微抛光。这些薄片被折叠卷在一起,成为摩基印第安人的主食。由于这道菜是用来招待我们的,而且看起来很干净,所以我们都吃了。这道菜有一种淡淡的新鲜面包味,一点也不难吃,尤其是加盐吃的时候。***房间的面积是 15 英尺乘 10 英尺,墙壁是用阿多巴木做的,隔板是用大梁做的,地板是用粘土铺的。一个角落里有壁炉和烟囱。一切都干净整洁。墙壁上或挂着兽皮、弓箭、箭筒、鹿角、毯子、衣物和装饰品,或摆放在架子上。另一头有一个槽,分成几个隔间,每个隔间里都有一块两三英尺见方的斜石板,用来磨玉米。在一间内室的凹处,堆放着大量的玉米穗。另一间内室似乎是睡觉的地方,但由于里面住的是女人,我们没有进去,不过印第安人似乎对我们仔细查看他们的住所和家具时表现出的好奇心很高兴。***然后,我们来到平台上,又走了一段台阶登上屋顶,在那里我们看到了一幅壮丽的全景图。* * *我们得知这里有七个城镇。每个普韦布洛都围绕着一个长方形的庭院而建,我们猜想庭院里有为水库提供水源的泉眼。外墙是石头砌成的,没有开口,要想进入内部,必须攀爬或撞击墙壁。连续的楼层向后退,一前一后。从第一层楼面通过活板门可以到达下层房间。房屋进深三间,向内部庭院开放。这样的设计既坚固又紧凑,但由于庭院是公用的,各楼层之间没有任何隔断,因此居住起来有一定的群体性 "。

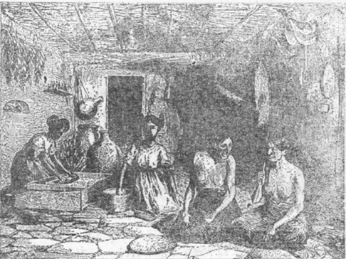

图3 摩基人的一间房

The above engraving was prepared for an article by Maj. Powell, on these Indians. Two rooms are shown together, apparently by leaving out the wooden partition which separated them, showing an extent of at least thirty feet. The large earthen water-jars are interesting specimens of Moki pottery. At one side is the hand mill for grinding maize. The walls are ornamented with bows, quivers, and the floor with water-jars, as described by Lieutenant Ives.

上述雕刻是鲍威尔少校为一篇关于这些印第安人的文章而准备的。图中两个房间连在一起,显然是去掉了分隔它们的木隔板,显示出至少 30 英尺的范围。大型土制水罐是莫基陶器的有趣标本。一侧是磨玉米的手磨房。正如艾夫斯中尉所描述的那样,墙壁上装饰着弓、箭筒,地板上装饰着水罐。

In places on the sides of the bluffs at this and other pueblos, Lieutenant Ives observed gardens cultivated by irrigation. “Between the two,” he remarks, “the faces of the bluff have been ingeniously converted into terraces. These were faced with neat masonry, and contained gardens, each surrounded with a raised edge so as to retain water upon the surface. Pipes from the reservoirs permitted them at any time to be irrigated.”

艾夫斯中尉观察到,这个普韦布洛和其它普韦布洛在靠悬崖边上的一侧有一些以灌溉耕作的园圃。"他说:"在这两处之间,悬崖的表面被巧妙地改造成了梯田。这些梯田由整齐的砖石砌成,内有园圃,每个园圃周围都有凸起的边缘,以便将水保留在地表。水库的水管可以随时灌溉这些园圃 "。

Fig. 27 shows one of two large adobe structures constituting the pueblo of Taos, in New Mexico. It is from a photograph taken by the expedition under Major Powell. It is situated upon Taos Creek, at the western base of the Sierra Madre Range, which forms the eastern border of the broad valley of the Rio Grande, into which the Taos stream runs. It is an old and irregular building, and is supposed to be the Braba of Coronado’s expedition.Some ruins still remain, quite near, of a still older pueblo, whose inhabitants, the Taos Indians affirm, they conquered and dispossessed. The two structures stand about twenty-five rods apart, on opposite sides of the stream, and facing each other. That upon the north side, represented in the above engraving, is about two hundred and fifty feet long, one hundred and thirty feet deep, and five stories high; that upon the south side is shorter and deeper, and six stories high. The present population of the pueblo, about four hundred, are divided between the two houses, and they are a thrifty, industrious, and intelligent people. Upon the east side is a long adobe wall, connecting the two buildings, or rather protecting the open space between them. A corresponding wall, doubtless, closed the space on the opposite side, thus forming a large court between the buildings, but, if so, it has now disappeared. The creek is bordered on both sides with ample fields or gardens, which are irrigated by canals, drawing water from the stream. The adobe is of a yellowish-brown color, and the two structures make a striking appearance as they are approached. Fire-places and chimneys have been added to the principal room of each family; but it is evident that they are modern, and that the suggestion came from Spanish sources. They are constructed in the corner of the room. The first story is built up solid, and those above recede in the terraced form. Ladders planted against the walls show the manner in which the several stories are reached, and, with a few exceptions, the rooms are entered through trap-doors by means of ladders. Children and even dogs run up and down these ladders with great freedom. The lower rooms are used for storage and granaries, and the upper for living rooms; the families in the rooms above owning and controlling the rooms below. The pueblo has its chiefs.

图 27 展示了构成新墨西哥州陶斯镇的两座大型土木结构建筑之一。这是鲍威尔少校率领的探险队拍摄的照片。它位于马德雷山脉西部底部的陶斯溪边,马德雷山脉是格兰德河宽阔河谷的东部边界,陶斯溪流就汇入了格兰德河。这是一座古老而不规则的建筑,据说是科罗纳多探险队所称的“布拉巴”。就在附近,还有一个更为古老的普韦布洛德的遗址,阿塔斯印第安人确认,他们征服并剥夺了那里的居民。这两座建筑相距约 25 英里,位于溪流的两侧,面对面。北侧的建筑如上图所示,长约 250 英尺,深 130 英尺,高五层;南侧的建筑较短,较深,高六层。布韦布洛现有人口约四百人,分别居住在这两座房子里,他们勤劳节俭,聪明伶俐。东侧有一道长长的土坯墙,连接着两座建筑,或者说是保护着两座建筑之间的空地。毫无疑问,对面也有一堵相应的墙,封闭了两座建筑之间的空地,从而在两座建筑之间形成了一个大庭院。溪流两侧是广阔的田地或花园,由引自溪流的水渠灌溉。土坯房呈黄褐色,走近这两座建筑,会让人眼前一亮。每个家庭的主要房间都加装了壁炉和烟囱;但很明显,它们都是现代的,而且是来自西班牙的建议。它们建在房间的角落里。第一层是坚固的建筑,上面的建筑呈阶梯状向后退。靠墙放置的梯子显示了到达几层楼的方式,除了少数例外,房间都是通过梯子从活门进入的。孩子们甚至连狗都可以自由地在梯子上跑上跑下。下面的房间用作储藏室和粮仓,上面的房间用作起居室;上面房间的家庭拥有并控制下面的房间。普韦布洛有自己的酋长。

The measurements of the two edifices were furnished to the writer in 1864 by Mr. John Ward, at that time a government Indian agent, by the procurement of Dr. M. Steck, superintendent of Indian affairs in New Mexico. Among further particulars given by Mr. Ward are the following: "The thickness of the walls of these houses depends entirely upon the size of the adobe and the way in which it is laid upon the wall; that is, whether lengthwise or crosswise. There is no particular standard for the size of the adobes. On the buildings in question the adobes on the upper stories are laid lengthwise, and will average about ten inches in width, which gives the thickness of the walls. On the first story or ground rooms the adobes are in most places laid crosswise, thus making the thickness of these walls just the length of the adobe, which averages about twenty inches. The width of an adobe is usually one-half its length, and the thickness will average about four inches. The floors and roofs are coated with mud mortar from four to six inches thick, which is laid on and smoothed over with the hand. This work is usually performed by women. When the right kind of earth can be obtained the floor can be made very hard and smooth, and will last a very long time without needing repairs. The walls both inside and out are coated in the same manner. On the inside, however, more care is taken to make the walls as even and smooth as possible, after which they are whitewashed with yesso or gypsum."

1864 年,时任政府印第安人代理人的约翰·沃德先生在新墨西哥州印第安人事务总监 M. 斯泰克博士的帮助下,向作者提供了这两座建筑的测量数据。沃德先生还提供了以下详细信息:"这些房屋墙壁的厚度完全取决于土坯的大小和在墙上铺设的方式,即纵向铺设还是横向铺设。土坯的大小没有特定的标准。在上述建筑中,上层的土坯是纵向铺设的,平均宽度约为 10 英寸,这就是墙壁的厚度。在第一层或底层房间,大部分土坯都是横向铺设的,因此这些墙壁的厚度与土坯的长度相同,平均约为 20 英寸。土坯墙的宽度通常是长度的二分之一,厚度平均约为四英寸。地板和屋顶涂有四到六英寸厚的泥浆,铺上泥浆后用手抹平。这项工作通常由妇女完成。如果能得到合适的泥土,地板就会变得非常坚硬和光滑,而且可以使用很长时间而无需修补。内外墙也是用同样的方法涂刷。不过,内墙要更加小心,尽可能使墙面平整光滑,然后用石膏粉粉刷"。

Several rooms on the ground floor were measured by Mr. Ward and found to be, in feet, 14 by 18, 20 by 22, and 24 by 27, with a height of ceiling averaging from 7 to 8 feet. In the second story they measured, in feet, 14 by 23, 12 by 20, and 15 by 20, with a height of ceiling varying from 7 to 7¼ feet. The rooms in the third, fourth, and fifth stories were found to diminish in size with each story. There is probably a mistake here, as the main longitudinal partition walls must have been carried up upon each other from bottom to top. A few of the doorways were measured and found to range from 2½ feet wide by 4½ feet high and 2 1/3 feet wide by 4 10/12 feet high. The scuttles or trap-doors in the floors, through which they descended into these rooms by means of ladders, were 3 feet by 2½, 3 feet by 2, and 1 10/12 by 2½ feet; and the window openings through the walls were, in inches, 14 by 14, 8 by 16, 16 by 20, and 18 by 18.

沃德先生对一楼的几个房间进行了测量,发现这些房间的面积分别为 14 乘 18 英尺、20 乘 22 英尺和 24 乘 27 英尺,天花板高度平均为 7 至 8 英尺。第二层房间的面积分别为 14 乘 23 英尺、12 乘 20 英尺和 15 乘 20 英尺,天花板高度从 7 英尺到 7¼ 英尺不等。第三层、第四层和第五层的房间面积逐层缩小。这很可能是一个错误,因为主要的纵向隔墙一定是自下而上相互承接的。我们对一些门洞进行了测量,发现它们的宽度从 2½ 英尺宽、4½ 英尺高到 2.1/3 英尺宽、4.10/12 英尺高不等。他们通过梯子下到这些房间的地板上的门洞或活门分别为 3 英尺乘 2.5 英尺、3 英尺乘 2 英尺和 1.10/12 英尺乘 2.5 英尺;穿过墙壁的窗洞的尺寸分别为 14 英寸乘 14 英寸、8 英寸乘 16 英寸、16 英寸乘 20 英寸和 18 英寸乘 18 英寸。

Mr. Ward then proceeds: “No room has more than two windows; very few have more than one. The back rooms usually have one or more round holes made through the walls from six to eight inches in diameter. These openings furnish the apartments with a scanty supply of light and air. The first story or the ground rooms are usually without doors or windows, the only entrance being through the scuttle-holes or doors in the roof, which are within the rooms comprising the story immediately above. These basement rooms are used for store-rooms. Those in the upper stories are the rooms mostly inhabited. Those located in the front part of the building receive their light through the doors and windows before described. The back rooms have no other light than that which goes in through the scuttle-holes and the partition walls leading from the front rooms; that is, where a room is so situated as to have both. Others again have no other light than that which enters through the holes already described. Such rooms are always gloomy. Some families have as many as four or five rooms, one of which is set apart for cooking, and is furnished with a large fire-place for the purpose. Those who have only two or three rooms usually cook and sleep in the same apartment, and in such cases they cook in the usual fire-place, which stands in one corner of the room. No perceptible addition has been made to either of the buildings for many years; and it is evident that after the death or removal of their owners they were entirely neglected. Those in good condition are still occupied. From the best information attainable the original buildings were not erected all at one time, but were added to from time to time by additional rooms, including the second, third, and more stories. There are no regular terraces, the roof of the rooms below answering that purpose. Thus it is that no entire circuit can be made around any one of these stories, the only thing that can be called a terrace being the narrow space left in front of some of the rooms from the roofs of the lower rooms."

沃德先生接着说 "没有一个房间有两扇以上的窗户,只有极少数房间有一扇以上的窗户。里屋的墙壁上通常有一个或多个直径在六到八英寸之间的圆孔。这些洞口为居室提供了稀少的光线和空气。第一层或底层房间通常没有门窗,唯一的入口是通过屋顶上的通风孔或门,这些通风孔或门就在紧接着上一层的房间内。这些地下室房间用作储藏室。上层的房间则是大多数人居住的房间。位于建筑物正面的房间通过前面所述的门窗采光。后面的房间除了从前面房间的窗户和隔墙透进来的光线外,就没有其他光线了;也就是说,如果一个房间的位置使这两种光线都有的话。还有一些房间除了从上述孔洞中透进来的光线外,没有其他光线。这样的房间总是阴沉沉的。有些家庭有多达四五个房间,其中一个房间专门用来做饭,并为此配备了一个大壁炉。那些只有两三个房间的家庭通常在同一个房间里做饭和睡觉,在这种情况下,他们就在通常的壁炉里做饭,壁炉就在房间的一个角落里。多年来,这两座建筑都没有明显的改建;很明显,在主人去世或搬走后,它们就完全被忽视了。那些状况良好的建筑仍有人居住。根据所能获得的最佳信息,最初的建筑并不是一次建成的,而是不时增加房间,包括第二层、第三层和更多层。这里没有规则的露台,下面房间的屋顶就是露台。因此,这些楼层中的任何一层都无法形成完整的环形,唯一可以称作露台的是一些房间前面从低层房间的屋顶上留出的狭窄空间"。

Mr. Ward seems to object to the word “terrace” in defining the platform left in front of each story as a means of access to its apartments and to the successive stories. It was used by the early Spanish writers to explain the same peculiarity found in many of the great houses in the pueblo of Mexico and elsewhere over Mexico, the roofs being flat and the stories receding from each other. While this platform is not in strictness a terrace, the term expresses this architectural feature with sufficient clearness. The two structures at Taos are large enough to accommodate five hundred persons in each, the inmates living in the Indian fashion. They were occupied in 1864 by three hundred and sixty-one Taos Indians.

沃德先生似乎反对用 "露台 "一词来定义每层楼房前面留出的平台,以作为通往其居室和连续楼层的通道。早期的西班牙作家用这个词来解释墨西哥布韦洛和墨西哥其他地方的许多大房子的相同特点,即屋顶是平的,层与层之间的距离是后退的。虽然从严格意义上讲,这种平台并不是露台,但这个词已经足够清楚地表达了这种建筑特征。陶斯的两座建筑各可容纳五百人,居住者以印第安人的方式生活。1864 年,有三百六十一名陶斯印第安人居住在这里。

"前面提到的米勒先生在谈到一般的部落时说:"每个露台都是通过木梯到达的,先从地面,然后再从下面的露台;下面房间的出入口是在上面房间的内侧,通过活板门和梯子。印度孩子和狗在梯子上跑上跑下的敏捷程度令人叹为观止。在这栋大房子里,房间与房间之间没有任何联系,每一排房间都是一户人家居住。最后这句话说得太笼统了,因为我们看到沃德先生已经给出了穿过隔墙的门的尺寸。这种门也将在随后的雕刻中展示出来。但毫无疑问的是,相互连通的横向房间数量很少,如果有家庭或群体的话,这些家庭或群体联合在一个公共家庭中,相互之间被坚固的隔墙隔开,这一事实将再次出现在尤卡坦的房屋建筑中。

In 1877, David J. Miller, esq., of Santa Fé, visited the Taos Pueblo at my request, to make some further investigations. He reports to me the following facts: The government is composed of the following persons, all of whom, except the first, are elected annually: 1. A cacique or principal sachem. 2. A governor or alcalde. 3. A lieutenant-governor. 4. A war captain, and a lieutenant war captain. 5. Six fiscals or policemen. “The cacique,” Mr. Miller says, “has the general control of all officers in the performance of their duties, transacts the business of the pueblo with the surrounding whites, Indian agents, etc., and imposes reprimands or severer punishments upon delinquents. He is keeper of the archives of the pueblo; for example, he has in his keeping the United States patent for the tract of four square leagues on which the pueblo stands, which was based upon the Spanish grant of 1689; also deeds of other purchased lands adjoining the pueblo. He holds his office for life. At his death, the people elect his successor. The cacique may, before his death, name his successor, but the nomination must be ratified by the people represented by their principal men assembled in the estufa.” In this cacique may be recognized the sachem of the northern tribes, whose duties were purely of a civil character. Mr. Miller does not define the duties of the governor. They were probably judicial, and included an oversight of the property rights of the people in their cultivated lands, and in rooms or sections of the pueblo houses. “The lieutenant-governor,” he remarks, “is the sheriff to receive and execute orders. The war captain has twelve subordinates under his command to police the pueblo, and supervise the public grounds,” such as grazing lands, the cemetery, estufas, &c. The lieutenant war captain executes the orders of his principal, and officiates for him during his absence, or in case of his disability. The six fiscals are a kind of town police. It is their duty to see that the catechism (Catholic) is taught in the pueblo, and learned by the children, and generally to keep order and execute the municipal regulations of the pueblo under the direction of the governor, who is charged with the duty of seeing to their execution.”

1877 年,圣菲的大卫·米勒(David J. Miller)律师应我的请求访问了陶斯普韦布洛,做了一些进一步的调查。他向我报告了以下事实:政府由以下人员组成,除第一位外,其余人员每年选举一次:1.一名卡西克即大首领。2.一名阿尔卡德,即长官。3. 一名副长官。4. 一名军事酋长和一名副军事酋长。5. 六名菲斯卡尔,即警察。"米勒先生说:"卡西克全面控制所有官员履行职责,与周围的白人、印第安人代理人等处理普韦布洛的事务,并对违法者进行训斥或严惩。他是普韦布洛档案的保管人,例如,他保管着普韦布洛所在的四平方英里土地的美国专利证书,该专利证书是根据 1689 年西班牙的赠与而授予的;他还保管着与普韦布洛毗邻的其他购买土地的契约。他终身任职。他去世后,人民选举他的继任者。卡西克在死前可以提出他的继任者,但他的提名必须得到的代表民众的埃斯图法集会的头人的批准。于此可见,卡西可被看作相当于北部部落的首领,其职责纯粹是行政性质的。米勒先生没有说明长官的职责。他们的职责可能是司法方面的,包括监督人们在耕地和普韦布洛房屋的房间或部分的财产权。"他说,"副长官是接受和执行命令的司法行政长官。军事酋长手下有 12 名下属,负责维持普韦布洛的治安和监督公共场所,"如牧场、墓地、河口等。副军事酋长执行军事酋长的命令,并在军事酋长不在或失去指挥能力时代行军事酋长职务。六名菲斯卡尔是一种城镇警察。他们的职责是监督教义(天主教)在普韦布洛的传授和儿童的学习,并在长官的指导下维持秩序和执行普韦布洛的市政法规,长官的职责是检察这方面工作的执行情况。

“The regular time for meeting in the estufa is the last day of December, annually, for the election of officers for the ensuing year. The cacique, governor, and principal men nominate candidates, and the election decides. There may also be a fourth nomination of candidates, that is, by the people. In the election, all adult males vote; the officers first, and then the general public. The officers elected are at the present time sworn in by the United States Territorial officials.”

"埃斯图法集会的时间照例是每年十二月的最后一天,以便选举下一年度的官员。卡西克、长官和主要官员提名候选人,然后由选举决定。也可能有第四个候选人提名,即由人民提名。在选举中,所有成年男子都要投票;首先是官员,然后是普通民众。当选的官员目前由美国领土官员宣誓就职"。

In this simple government we have a fair sample, in substance and in spirit, of the ancient government of the Pueblo Indians of New Mexico. Some modification of the old system may be detected in the limitation of officers below the grade of cacique to one year. From what is known of the other pueblos in New Mexico, that of Taos is a fair example of all of them in governmental organization at the present time. They are, and always were, essentially republican, which is in entire harmony with Indian institutions. I may repeat here what I have ventured to assert on previous occasions, that the whole theory of governmental and domestic life among the Village Indians of America from Zuñi to Cuzco can still be found in New Mexico.

在这个简单的政府中,我们看到了新墨西哥州普韦布洛印第安人古代政府的实质和精神的一个公平样本。从卡西克(cacique)级别以下的官员任期为一年的限制中,我们可以发现对旧制度的一些修改。根据我们对新墨西哥州其他普韦布洛的了解,塔奥斯是目前所有普韦布洛政府组织的典范。他们现在是,而且一直是,基本上是共和制,这与印第安人的制度完全一致。我可以在这里重复我在以前场合大胆断言过的话,即从祖尼到库斯科的美洲乡村印第安人的整个政府和家庭生活理论仍然可以在新墨西哥州找到。

The representation of a room in this pueblo, Figure 14.2, is from a sketch by Mr. Galbraith, who accompanied Major Powell’s party to New Mexico.

图 14.2 所示的是这个布韦布洛的一个房间,出自随鲍威尔少校一行前往新墨西哥的加尔布雷思先生的素描。

What Mr. Miller refers to as “property rights and titles” and “ownership in fee” of land, is sufficiently explained by the possessory right which is found among the northern Indian tribes. The limitations upon its alienation to an Indian from another pueblo, or to a white man, not to lay any stress upon the absence of written titles or conveyances of land which have been made possible by Spanish and American intercourse, show very plainly that their ideas respecting the ownership of the absolute title to land, with power to alienate to whomsoever the person pleased, were entirely above their conception of property and its uses. All the ends of individual ownership and of inheritance were obtained through a mere right of possession, while the ultimate title remained in the tribe. According to the statement of Mr. Miller, if the father dies, his land is divided between his widow and children, and if a woman, her land is divided equally between her sons and daughters. This is an important statement, because, assuming its correctness, it shows inheritance of children from both father and mother, a total departure from the principles of gentile inheritance. In 1878 I visited the Taos pueblo. I could not find among them the gens or clan,25 and from lack of time did not inquire into their property regulations or rules of inheritance. The dozen large ovens I saw while there near the ends or in front of the two buildings, each of which was equal to the wants of more than one family, were adopted from the Spanish. They not unlikely had some connection with the old principle of communism.

米勒先生所说的 "产权和所有权 "以及土地的 "有偿所有权",在北部印第安部落的占有权中得到了充分的解释。印第安人将土地转让给另一个普韦布洛的印第安人或白人时受到限制,更不用说西班牙和美国的交往使他们没有书面的土地所有权或转让权,这些都非常清楚地表明,他们对土地绝对所有权的观念,以及将土地转让给任何人的权力,完全超越了他们对财产及其用途的概念。个人所有权和继承权的所有目的都是通过单纯的占有权获得的,而最终的所有权仍然属于部落。根据米勒先生的说法,如果父亲去世,他的土地由他的遗孀和子女平分;如果是妇女,她的土地由她的儿子和女儿平分。这是一个重要的陈述。因为假定这一说法是正确的,它表明子女的继承权来自父亲和母亲,这完全背离了外邦人的继承原则。1878 年,我访问了陶斯普韦布洛。我在他们中间找不到宗族或氏族,25 而且由于时间不够,也没有调查他们的财产条例或继承规则。我在那里的两座建筑物的两端或前面看到了十几个大烤炉,每个烤炉都能满足一个以上家庭的需要,这些烤炉都是从西班牙人那里继承来的。它们与古老的共产主义原则不无关系。

It will prove a very difficult undertaking to ascertain the old mode of life three hundred and fifty years ago in New Mexico, Mexico, and Central America, as it was then in full vitality, a natural outgrowth of Indian institutions. The experiment to recover this lost condition of Indian society has not been tried. The people have been environed with civilization during the latter portion of this period, and have been more or less affected by it from the beginning. Their further growth and development was arrested by the advent of European civilization, which blighted their more feeble culture. Since their discovery they have steadily declined in numbers, and they show no signs of recovery from the shock produced by their subjugation. Among the northern tribes, who were one Ethnical Period below the Pueblo Indians, their social organization and their mode of life have changed materially under similar influences since the period of discovery. The family has fallen more into the strictly monogamian form, each occupying a separate house; communism in living in large households has disappeared; the organization into gentes has in many cases fallen out or been rudely extinguished by external influences; and their religious usages have yielded. We must expect to find similar and even greater changes among the Village Indians of New Mexico. The white race were upon them in Mexico and New Mexico a hundred years earlier than upon the Indian tribes of the United States. But, as if to stimulate investigation into their ancient mode of life, some of these tribes have continued through all these years to live in the same identical houses occupied by their forefathers in 1540 at Acoma, Jemez, and Taos. These pueblos were contemporary with the pueblo of Mexico captured by Cortez in 1520. The present inhabitants are likely to have retained some part of the old plan of life, or some traditionary knowledge of what it was. They must retain some of the usages and customs with respect to the ownership and inheritance of sections of these houses, and of the limitations upon the power of sale that they should not pass out of the kinship. The same also with respect to sections of the village garden. All the facts with respect to their ancient usages and mode of life should be ascertained, so far as it is now possible to do so from the present inhabitants of these pueblos. The information thus given will serve a useful purpose in explaining the pueblos in ruins in Yucatan and Central America, as well as on the San Juan, the Chaco, and the Gila.

要确定三百五十年前新墨西哥州、墨西哥和中美洲的古老生活方式是非常困难的,因为当时的生活方式充满活力,是印第安人制度的自然产物。恢复这种失落的印第安社会状态的实验还没有尝试过。在这一时期的后半段,人们一直处于文明的环境中,从一开始就或多或少地受到文明的影响。欧洲文明的到来阻碍了他们的进一步成长和发展,削弱了他们较为脆弱的文化。自从被发现以来,他们的人数持续下降,而且没有从被征服的打击中恢复过来的迹象。在比普韦布洛印第安人低一个民族时期的北部部落中,自发现以来,他们的社会组织和生活方式也在类似的影响下发生了实质性的变化。家庭更多地变成了严格的一夫一妻制形式,每个人都住在单独的房子里;在大户人家生活的公社主义已经消失;在许多情况下,氏族的组织已经消失或被外部影响粗暴地消灭;他们的宗教习俗也已经屈服。我们必须期待在新墨西哥的乡村印第安人中发现类似甚至更大的变化。墨西哥和新墨西哥州的白人部落比美国的印第安部落早一百年就出现了。但是,为了激发人们对其古老生活方式的探究,这些部落中的一些人多年来一直住在他们的祖先于 1540 年在阿科马、杰梅斯和陶斯居住过的相同的房子里。这些部落与科尔特斯 1520 年占领的墨西哥部落是同时代的。现在的居民很可能还保留着旧生活计划的某些部分,或对旧生活计划的某些传统知识。他们一定保留了一些关于这些房屋的所有权和继承权的习俗和惯例,以及对出售权的限制,即这些房屋不得从亲属关系中流出。他们对村落园圃的土地也一定是这样处理的。只要现在有可能,就应该向这些村落的现任居民了解有关其古老习俗和生活方式的所有事实。这样提供的信息对于解释尤卡坦和中美洲以及圣胡安河、查科河和吉拉河上的废墟中的普韦布洛很有帮助。

At the time of their discovery the Pueblo Indians of New Mexico generally worshipped the sun as their principal divinity. Although under constraint they became nominally Roman Catholic, they still retain, in fact, their old religious beliefs. Mr. Miller has sent me some information upon this subject concerning the pueblos of Taos, Jemez, and Zia.

新墨西哥州的普韦布洛印第安人在被发现时,通常把太阳作为他们的主神来崇拜。虽然在强迫之下,他们名义上成为了罗马天主教徒,但事实上,他们仍然保留着古老的宗教信仰。米勒先生给我寄来了一些有关陶斯、杰梅斯和齐亚等普韦布洛印第安人的资料。

“Before the Spaniards forced their religion upon the people, the pueblo of Taos had the Sun for their God, and worshipped the Sun as such. They had periodical assemblages of the authorities and the people in the estufas for offering prayers to the Sun, to supplicate him to repeat his diurnal visits, and to continue to make the maize, beans, and squashes grow for the sustenance of the people. ‘The Sun and God,’ said the governor (Mirabal) to me, ‘are the same. We believe really in the Sun as our God, but we profess to believe in the God and Christ of the Catholic Church and of the Bible. When we die, we go to God in Heaven. I do not know whether Heaven is in the Sun, or the Sun is Heaven. The Spaniards required us to believe in their God, and we were compelled to adopt their God, their church, and their doctrines, willing or unwilling. We do not know that under the American Government we may exercise any religion we choose, and that the National Government and the church government are wholly disconnected. We have very great respect and reverence for the Sun. We fear that the Sun will punish us now, or at some future time, if we do evil. The modern pueblos have the Sun religion really, but they profess the Christian religion, of which they know nothing but what the Catholic religion teaches. They always believed that Montezuma would come again as the messiah of the pueblo. The Catholic religion has been so long outwardly practiced by the people that it could not now, they think, be easily laid aside, and the old Sun religion be established, because it is looked upon as established by the law of the land, and therefore necessarily practiced. Nevertheless, the Indians will always follow and practice, as they do, both religions. If,’ said the governor, ‘one Indian here at this pueblo were to declare that he intended to renounce and abandon the religion of his fathers (the worship of the Sun) and adopt the Christian religion as his only faith, and another Indian were to declare that he intended to repudiate the Christian religion and adopt and practice only the Sun religion, the former would be expelled the pueblo, and his property would be confiscated, but the other would be allowed to remain with all his rights”.

"在西班牙人强迫人们信奉他们的宗教之前,陶斯普韦布洛人以太阳为神,并以此崇拜太阳。他们定期在河口集会,向太阳祈祷,祈求太阳昼伏夜出,继续种植玉米、豆类和南瓜,供人们食用。总督(米拉瓦尔)对我说:"太阳和上帝是一样的。我们真的相信太阳是我们的上帝,但我们自称相信天主教会和《圣经》中的上帝和基督。我们死后,会去天堂见上帝。我不知道天堂是在太阳里,还是太阳就是天堂。西班牙人要求我们信仰他们的上帝,我们被迫接受他们的上帝、他们的教会和他们的教义,不管愿不愿意。我们不知道,在美国政府的管辖下,我们可以选择信奉任何宗教,而且国家政府和教会政府是完全分离的。我们非常尊重和敬畏太阳。我们担心,如果我们作恶,太阳现在或将来会惩罚我们。现代的普韦布洛人信奉的是真正的太阳教,但他们信奉的是基督教,他们对基督教一无所知,只知道天主教的教义。他们一直相信蒙特祖玛会作为普韦布洛的救世主再次降临。长期以来,人们一直公开信奉天主教,他们认为现在不可能轻易放弃天主教,而建立古老的太阳教,因为人们认为天主教是由国家法律确立的,因此必须信奉。尽管如此,印第安人还是会一如既往地信奉这两种宗教。总督说:"如果这个普韦布洛的一个印第安人宣布他打算放弃和抛弃他祖先的宗教(太阳崇拜),并将基督教作为他唯一的信仰,而另一个印第安人宣布他打算放弃基督教,只信奉太阳教,那么前者将被驱逐出普韦布洛,他的财产也将被没收,但另一人将被允许留下,并享有他的所有权利。"

“There are three old men in the pueblo whose duty it is to impart the traditions of the people to the rising generation. These traditions are communicated to the young men according to their ages and capacities to receive and appreciate them. The Taos Indians have a tradition that they came from the north; that they found other Indians at this place (Taos) living also in a pueblo; that these they ejected after much fighting, and took and have continued to occupy their place. How long ago this was they cannot say, but it must have been a long time ago. The Indians driven away lived here in a pueblo, as the Taos Indians now do.”

"普韦布洛有三位老人,他们的职责是将本民族的传统传授给下一代。这些传统会根据年轻人的年龄和接受能力传授给他们。陶斯印第安人有这样一个传统:他们来自北方;他们在这个地方(陶斯)发现其他印第安人也住在一个普韦布洛;经过一番争斗,他们把这些印第安人赶了出去,占据了他们的地方,并一直居住至今。他们说不清这是多久以前的事,但肯定是很久以前的事了。被赶走的印第安人住在这里的一个村落里,就像现在的陶斯印第安人一样。

Mr. Miller also communicates a conversation had with Juan José, a native of Zia, and José Miguel, a native of Pecos, but then (December, 1877) a resident of the pueblo of Jemez, which he wrote down at the time, as follows: “Before the Spaniards came, the religion of Jemez, Pecos and Zia, and the other pueblos, was the Montezuma religion. A principal feature of this religion was the celebration of Dances at the pueblo. In it, God was the sun. Seh-un-yuh was the land the Pueblo Indians came from, and to it they went when dead. This country (Seh-un yuh) was at Great Salt Lake. They cannot say whether this lake was the place where the Mormons now live, but it was to the north. Under this great lake there was a big Indian Pueblo, and it is there yet.The Indian dances were had only when prescribed by the cacique. The Pueblo Indians now have two religions, that of Montezuma, and the Roman Catholic. The Sun, Moon, and Stars were Gods, of which the greatest and most potent was the Sun; but greater than he was Montezuma. In time of drought, or actual or threatened calamity, the Pueblo Indians prayed to Montezuma, and also to the Sun, Moon, and Stars. The old religion (that of Montezuma) is believed in all the New Mexican pueblos. They practice the Catholic religion ostensibly; but in their consciences and in reality the old religion is that of the pueblos. The tenets of the old religion are preserved by tradition, which the old men communicate to the young in the estufas. At church worship the Pueblo Indians pray to God, and also to Montezuma and the Sun; but at the dances they pray to Montezuma and the Sun only. During an actual or threatened calamity the dances are called by the cacique. They have two Gods; the God of the Pueblos, and the God of the Christians. Montezuma is the God of the Pueblo.”

米勒先生还提供了他与齐亚人胡安·何塞和佩科斯人何塞·米格尔的一段对话,何塞·米格尔当时(1877 年 12 月)是杰梅斯村的居民,他当时写下了这段对话,内容如下:"在西班牙人到来之前,杰米斯、佩科斯和齐亚以及其他部落的宗教是蒙特祖马教。这种宗教的一个主要特征是在部落里举行舞会。在这种宗教中,神是太阳。Seh-un-yuh 是普韦布洛印第安人的故乡,他们死后都会去那里。这个国家(Seh-un-yuh)位于大盐湖。他们说不清这个湖是否就是摩门教徒现在居住的地方,但它就在北面。在这个大湖下面有一个很大的印第安普韦布洛,现在还在那里。印第安人的舞蹈只有在卡西克规定的情况下才举行。普韦布洛印第安人现在有两种宗教,一种是蒙特祖玛教,另一种是罗马天主教。太阳、月亮和星星是神,其中最伟大、最有力量的是太阳,但比他更伟大的是蒙特祖玛。在干旱、实际或可能发生灾难的时候,普韦布洛印第安人会向蒙特祖玛以及太阳、月亮和星星祈祷。新墨西哥州的所有部落都信奉古老的宗教(蒙特祖玛教)。他们表面上信奉天主教,但实际上在他们的意识中和现实中,旧宗教就是普韦布洛人的宗教。古老宗教的教义通过传统得以保留,并由老人在埃斯图法传授给年轻人。在教堂礼拜时,普韦布洛印第安人向上帝祈祷,也向蒙特祖玛和太阳祈祷;但在舞会上,他们只向蒙特祖玛和太阳祈祷。在发生或可能发生灾难的时候,舞会由卡西克召集。他们有两个神:普韦布洛人的神和基督徒的神。蒙特祖玛是普韦布洛人的神。”

This account of the Sun worship of the Taos Indians, in which is intermingled that of Montezuma, and the further account of the worship of Montezuma at the pueblos of Zia and Jemez, with the recognition of the worship of the Sun, Moon, and Stars, are both interesting and suggestive. It is probable that Sun worship is the older of the two, while that of Montezuma, as a later growth, remained concurrent with the other in all the New Mexican pueblos without superseding it. In this supernatural person, known to them as Montezuma, who was once among them in bodily human form, and who left them with a promise that he would return again at a future day, may be recognized the Hiawatha of Longfellow’s poem, the Ha-yo-went’-ha of the Iroquois. It is in each case a ramification of a widespread legend in the tribes of the American aborigines, of a personal human being, with supernatural powers, an instructor of the arts of life; an example of the highest virtues, beneficent, wise, and immortal.

关于陶斯印第安人的太阳崇拜(其中夹杂着蒙特祖玛崇拜)的记载,以及在齐亚和杰米斯普韦布洛对蒙特祖玛崇拜的进一步记载,还有对太阳、月亮和星星崇拜的认可,这些记载既有趣又具有启发性。太阳崇拜很可能是这两种崇拜中较早的一种,而蒙特祖马崇拜则是后来发展起来的,在新墨西哥州所有的普韦布洛中与另一种崇拜同时存在,但并没有取而代之。在这个被他们称为蒙特祖玛的超自然人身上,可以看到朗费罗诗歌中的夏瓦塔(Hiawatha)和易洛魁人哈-约-温-特哈(Ha-yo-went'-ha)。在每一种情况下,它都是美洲原住民部落中广泛流传的一个传说的延伸,传说中的人具有超自然的力量,是生活艺术的指导者,是最高美德的典范,是仁慈、智慧和不朽的。

“They have,” remarks Mr. Miller, “one curious custom which has always been observed in the pueblo. It is for some one (sometimes several simultaneously) to seclude themselves entirely from the outer world, abstaining absolutely from all personal communication with others, and devoting themselves solely to prayer for the pueblo and its inhabitants. This seclusion lasts eighteen months, during which they are furnished daily, by a confidential messenger, with a little food, just enough to preserve life, and during which time they may not even inquire about their wives or children or be told anything of them though the messenger may know that some of them are sick or have died. The food the recluse is permitted to use is corn, beans, squashes, and buffalo and deer meat; that is, such food as was used before the coming of the Spaniards. This religious seclusion is in honor of the Sun. It is one of the rites of the ancient religion of the Pueblo, preserved and practiced now. One of the old men I talked with said that he had himself the previous year emerged from this hermitage; three others were now in, they having retired to exile in February, 1877, and will emerge in August, 1878, then to learn the news of the previous year and a half.”

"米勒先生说:"他们有一个奇特的习俗,在普韦布洛一直得到遵守。那就是由某个人(有时是几个人同时)完全与外界隔绝,绝对不与他人进行任何个人交流,一心一意为普韦布洛及其居民祈祷。这种隐居生活持续十八个月,在此期间,他们每天由一名密使提供少量食物,仅够维持生命,在此期间,他们甚至不能打听自己妻子或孩子的消息,也不能被告知他们的任何情况,尽管密使可能知道他们中有人生病或死亡。隐居者可以使用的食物是玉米、豆类、地瓜、水牛肉和鹿肉,也就是西班牙人来之前使用的食物。这种宗教隐居是为了纪念太阳。这是普韦布洛人古老宗教的仪式之一,现在仍被保留和奉行。与我交谈的一位老人说,他自己是在前一年从这个隐居地出来的;现在还有另外三个人在里面,他们是在 1877 年 2 月退隐流亡的,将在 1878 年 8 月出来,然后了解前一年半的消息"。