路易斯·亨利·摩尔根《美洲原住民的房屋和家庭生活》(一)

字号:T|T

2024-08-27 08:58 来源:建筑遗产学刊

读路易斯·亨利·摩尔根《美洲原住民的房屋和家庭生活》

史冬辉

路易斯·亨利·摩尔根(Lewis Henry Morgan),于1818年11月21日出生于美国纽约州中部奥罗拉村的一个农庄,该农庄位置相距印第安种族易洛魁人栖居地不远,也为他后来的研究埋下伏笔。优渥的家庭环境让他受到了良好教育。他于1840年以优异成绩毕业于纽约州罗彻斯特联合学院,并于1842年获得律师职业资格。并且是终身以律师为职业的美国人类学家、社会学家,着重对于史前人类文明特别是氏族政治制度与家庭习俗进行了研究,曾任美国“科学发展协会”主席、美国国家科学院院士。

摩尔根长期研究印第安人的社会制度,对人类的婚姻、亲属制度、氏族制度作了大量的研究,并以文化进化论和功能主义的双重视角将古代社会分成不同的发展时期,以此来研究其中的文化现象。但他的贡献却远不止于此。他从易洛魁人当中发现的特殊亲属制度出发,在密歇根州北部的印第安人中发现实质相同的制度和称呼,根据印度部分地区沿用的亲属关系术语,证明印第安人源自亚洲,1870年他发表了《血亲和姻亲制度》一书,对亲属关系作了精辟的论述,为研究家庭史“开辟了一条新的研究途径及进一步窥探人类史前史的可能”,引起当时人们对社会发展研究的兴趣。1872年他又发表了一部关于澳大利亚亲属关系的人类学著作。1877年他根据自己40年的研究、观察和搜集材料,写出了他的主要著作《古代社会》。发展了文化进化的理论。是对文明的起源和进化所作的最早的、重大的科学论述。书中重视文化的进化性质,提出社会变化的革命性质,预言了社会制度向比较公平化发展。1881年《美洲原住民的房屋和家庭生活》,是《古代社会》的续篇:从房屋建筑结构、布局和住房分配研究美洲土著居民的社会生活,看到家庭和社会组织的进化,而这些又和生产技术的进步密切相关。他也因此成为第一个将视角转向建筑的人类学家,他的这个视角转变,为我们带来了研究建筑的丰富视野。不仅如此,他以非凡探索和扎实的调查,几乎影响了19世纪及以后的人们的研究方法。

摩尔根从1818年出生时起,至1844年迁居至纽约州罗彻斯特开设律所,一直居住在纽约州中部奥罗拉村,该村落距离印第安种族多个部落的栖居地不远。1929-1931年,美国发生经济危机。那些年头,商业萧条,诉讼业务不多,摩尔根在其闲暇之时参加了一个由少数思想激进青年组成的秘密文学社“Gordian Knot”,社员们发表论文,讨论当下的深奥问题。1843年,在摩尔根主导下,该文学社转变为一个研究印第安种族易洛魁人的学会“New order of the Iroquois”(学界译为“易洛魁新秩序”/“大易洛魁社”),其宗旨在于“The study and perpetuation of Indian lore, the education of the Indian tribes, and the reconciliation of these tribes with the conditions imposed by civilization”(研究和延续印第安人的传说,教育印第安部落,并使这些部落与文明强加的条件和解)。或许是家庭位置的原因和人类学家的“使命”使得摩尔根天然对其相近的易洛魁文明有了浓厚的兴趣,这也为他的研究奠定了基础。从小到大,摩尔根亲身见证了印第安种族遭受的磨难。也因此更加珍视当时正迅速消逝的印第安文明,并着力改变这一现状。一方面,摩尔根积极研究和向世人推介印第安文化,让人们了解和产生同情。摩尔根走入印第安人部落观察他们的生活方式、风俗习惯,并着力于研究印第安人社会的组织结构、姻亲关系、氏族制度,相继发表了14封《易洛魁人的通信》,以及撰写了专著《易洛魁联盟》《人类家族的血亲和姻亲制度》《古代社会》《美洲土著的房屋与家庭生活》等,它们全面而又深刻地刻画了印第安人单纯质朴的原始氏族社会。另一方面,摩尔根积极采取实际行动,帮助印第安人解决诸多的现实问题。摩尔根展现了作为社会和人类学家对于社会的责任;他这一时期的著作,生动形象的展示了古代社会的一些方面,从而让我们对人类古老的文明有了深刻的认知。

摩尔根做调查研究,是一丝不苟、严谨认真的,力求真实准确,对于客观事实非常尊重,因此他被誉为“忠实的科学调查工作者”。这是值得我们学习和借鉴的。摩尔根对于调查对象提供的资料,很注意区分哪些是亲身经历的第一手资料,哪些是“道听途说”的;他不满足于“听”,更注重“参与式观察”,他所描写的印第安人习俗、仪式乃至游戏,大都是他亲眼观察到的真实情况。由于同情印第安人,支持印第安人为谋求生存而作的斗争,摩尔根遭受到了不少反对者的刁难,他们想方设法寻找他的错谬,特别要挑剔他的调查事实的错谬;但事实证明,错谬的是他们自己,而不是摩尔根。

除了“听”“参与式观察”之外,摩尔根还使用了在当时很显独特的调查方法——“表格调查”。摩尔根精心设计了一份详细的调查表格寄往世界各地,通过美国驻世界各地的使馆、传教士和有关的人,对当地的民族进行调查。这个范围广阔的调查历时10年之久,为摩尔根提供了丰富多样的素材资料。随着素材资料的积累,问题日益明确,不寻常的发现常常使摩尔根处于极度兴奋之中,他有时甚至关闭了律师事务所,埋头研究他想要探索和思考的问题。

一个时代的新世界观创造者似乎总是成为下一个时代的替罪羊。不可否认,摩尔根的某些思想观念存在错误,但是将之放入那个时代和背景下,甚至对于今天,他的影响都是深远的。摩尔根是一个出色的人类和社会学家,用身体力行教会我们如何去研究。

本篇文献选自摩尔根的《美洲原住民的房屋和生活方式》中的导论部分和第六章新墨西哥定居印第安人的房屋。文章导论部分以批判的眼光正视摩尔根的地位及其带来的影响,同时也指出了其存在的不足。进而为我们介绍了摩尔根对于印第安人房屋的描述和分析,从建筑的角度联系到社会组织,从而印证他关于文化进化论的观点,并希望以此对印第安人的社会结构做出解读。

摩尔根在这本书中所谈的是一个基本问题:家庭建筑向人类学者——无论是民族学者还是考古学者——在社会组织方面显示了什么,社会组织又如何与生产技术体系和生态学的调整相结合,从而影响了家庭建筑和公共建筑?

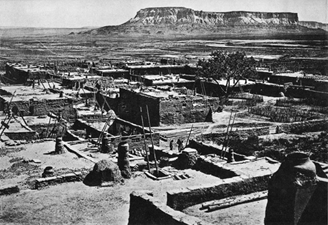

首先,摩尔根为我们描述了村居印第安人的房屋和生活方式。摩尔根认为村居印第安人处在中级野蛮社会,他们的房屋建筑与前两个阶段相比(蒙昧社会和低级野蛮社会),明显建筑技术要高一些。这个时期的典型建筑是新墨西哥地区的普韦布洛式房屋,该地区的人们已经开始使用土坯或石头建造房子。同时,村居印第安人的家屋规模也逐渐扩大,家屋不再限于一层,它们从两层到六层皆有。这些房屋是随着人口的增加而逐渐建立起来的,且上面的各层是往后缩的,呈阶梯状分布,可经由室外楼梯进入每一层。这些房屋的第一层一般是封闭式的,仅从二层平台可以进入摩尔根认为这样的设计是为防御敌人的进攻。对于他们的生活方式,他提到新墨西哥现在的村居印第安人,或至少是其中的一部分人,仍按照原来的方式制作陶器和纺纱织布,并住在古老的房屋里。他们中的一些人,如摩基人和拉古纳人,是按照氏族组织的,并由酋长理事会管理,每个村子都是独立和自治的。他们遵守北方印第安人普遍实行的好客原则,提出他们或许过着“共产主义”生活。

紧接着他对祖尼镇的房屋及人们的生活进行了详细的描述。在这里摩尔根首先提到了这些建筑是新墨西哥州所有土著房屋的典型代表。它们有两个主要特点:第一,墨西哥常见的阶梯式建筑形式,房屋顶部是居住者的社交聚会场所;第二,为了安全起见,地面层是封闭的。在祖尼人的普韦布洛式房屋中,每个家庭可以占有多个房间,这些房间里又有一个用于全家人工作、吃饭和睡觉的大房间。祖尼社会虽已出现阶级分化,但是成员之间并没有明显的社会界限。虽然富裕之人不愿意住在上层,但是也有官员由于其工作需要而住在上层。

同时,他也对陶斯普韦布洛和摩基普韦布洛的房屋大小,组合方式,建造材料、空间布局和使用人群,以及其中人们所吃的食物进行了论述。从论述表明印第安人主要的房屋形式和使用材料是如何根据地点不同做相应变化的,人们是如何在这座房屋里完成家庭生活,如摩尔根提出的“好客的原则”是如何展现的,对于“共产主义式生活”是如何实现的。

摩尔根认为,印第安人的建筑虽然在材料、规模、形状等方面存在差异,但是它们却都说明了一个事实,“家庭在各个发展阶段是个很软弱的组织,其力量不足以单独对付生活斗争,因此要几个家庭组成大家户以求得庇护。”这是摩尔根对印第安人房屋建筑的主要分析方向。在摩尔根看来,这些家屋建筑就本身而言价值并不大,但是通过将不同社会发展阶段的建筑形式进行对比,特别是中级野蛮社会以前的建筑与村居印第安人的建筑之间的比较,就会显示出其意义。他希望在对建筑的研究中呈现出原始社会结构空间面貌,也就是发现建筑背后的社会组织是如何影响建筑的,同时建筑和生活方式的改变又对社会组织形成了哪些影响。

最后摩尔根对新墨西哥地区这些普韦布洛的居民的信仰进行了阐述。他认为人们或多或少还保存着对于原始太阳神的崇拜,虽然会被天主教等教派“入侵”但是只不过是表面的屈服。但未对仪式或是其他细节进行描述,在这里也可以看到摩尔根关心的是现象背后的社会组织、氏族等问题而非其他方面。

摩尔根的这篇著作,不仅对他所深耕的人类学和社会学拥有深刻的影响,而且由于他的研究视角对准建筑,也为我们研究建筑打开新的世界的大门。综合来看文献具有如下几个方面的影响:

文献详细描述了美洲原住民不同部落的住房建筑类型、建造技术和家庭生活方式。通过对这些细节的深入探索,展现了美洲原住民社会的文化多样性和地域特色。这种呈现不仅帮助读者了解和尊重不同文化群体的独特性,也促进了跨文化交流和理解。同时,摩尔根所描述的家屋并非只是一些核心家庭的简单结合,更不是因社会关系建立起来的简单扩展家庭,它是社会成员在民主原则的指导下组织起来的社会。摩尔根所关注的并非是家屋社会中的家庭如何分工合作、家庭如何构成更大的地域群,而是在说明这些家庭如何通过民主原则得以联合。这也是对他所提出的文化进化论的进一步佐证。

文献中涉及的建筑技术和材料选择,如何与环境适应和生存策略密切相关。从新墨西哥北部到南部,这些建筑展示了原住民社区如何利用当地资源,建造适应其生活方式和自然环境的住房。这种探索不仅有助于理解古代技术如何塑造社会和文化,也对现代研究风土建筑提供了启示。建筑某些方面作为文化的产物,凝结了所生活在里面的人全部记忆和空间。通过对其细致的研究,以更深的角度,展现了建筑使用的场景和他们背后的社会组织和权力结构,从而丰富了对于建筑的理解,也是对于我们理解风土建筑的内涵做了有力的证明。

《美洲原住民的房屋和家庭生活》

路易斯·亨利·摩尔根

Only a handful of nineteenth-century social thinkers has had so extensive an impact on the twentieth century as has Lewis H. Morgan. All remembered students of society have influenced their societies in at least two ways: one is direct and results from their contribution to social science or philosophy; the other is covert and changes the matrix in terms of which whole cultures view the world and society. The two influences might be seen as the scientific battlefront and the fifth column. With few scholars is it so vital to make clear the distinctions between the scientist and the fifth columnist as it is with Morgan.

像路易斯·摩尔根一样对二十世纪有巨大影响的十九世纪社会思想家,寥寥无几。所有知名的社会学者至少以两种途径对其社会产生影响:一种是直接的,即由他们对于社会科学和哲学的贡献直接产生影响;另一种是较为隐晦的,它改变了整个文化对世界和社会所持的观点。可将这两种影响看作是科学战线和第五纵队。对于一些学者来说,要分清一位学者是真正的科学家还是第五纵队是最为重要的,对于研究摩尔根的学者同样如此。

Morgan’s Position and His Influence

摩尔根的地位和他的影响

It is well known that Morgan lived the life of a practical lawyer and businessman in Rochester, New York, making extensive ethnological investigations on his own time and for the most part at his own expense.1 He stayed outside the academic whirlpool (Morgan turned down an “offer” from Cornell), although he was closely associated with the museums of the state of New York and with the Bureau of American Ethnology in its early days under Powell. Morgan thought of himself as a scientist—one of his most eloquent pleas is the one for a new and scientific ethnography that appears at the end of this book. His social science, although it contains errors of fact and interpretation, was “right,” both in the sense that it created channels within which the subject could move and also in the further sense that its tenets changed the images of self-perception current in the Western world. A man can fittingly be held responsible for his scientific work; he cannot of course be held responsible for the version that trickles into common culture.

被我们熟知的是,摩尔根是生活在纽约州的罗切斯特执业的律师和实业家。但同时他也在业余时间进行广泛的民族学调查,并且调查的大部分花费都是由他自己支付的。尽管他与纽约州的许多博物馆以及在鲍威尔主持下的早期美国民族学馆有很多密切的联系,他仍然置身于学术界漩涡之外(摩尔根谢绝过康奈尔大学的“聘请”)。摩尔根认为自己是一个科学家——他的一个最令人向往的约许,就是在本书末尾提到的要建立新的、科学的民族学。他的社会科学,尽管在对事实的陈述和解释上有一些错误,但不可否认某种程度他是正确的。因为他的社会科学著作建立了改学科可以遵循前进的途径,而且他的创见改变了流行于西方世界并导源于自我观察的原则。要求一个人对他的科学研究结果负责是正确的,但不应要求他也必须为他渗透到共同文化中的见解负责。

Morgan was one of the primary inspirations of Marx and Engels. Engels’ book on the family is Morgan, with minor modifications. Marx took extensive notes for, but never wrote, a book on Morgan’s theories (White, op. cit., p. xxxiii). Ancient Society has never been out of print since its original publication in 1877; it has been kept in the public eye by socialist or communist presses. Yet, as White has pointed out, Morgan was a child of the bourgeois, not the communist, revolution. He never doubted that the American system, as he knew it, was the summum bonum of social organization, as the closing few pages of this book clearly indicate.

摩尔根是马克思和恩格斯最初灵感的来源。恩格斯关于家庭的著作是来自摩尔根,但做了少量修改。马克思对摩尔根的理论做了大量笔记,但是没有写一部关于他的理论的书。(怀特的《导言》XXXIII页)。《古代社会》自1877年首次出版以来从未绝版。由于社会学者和共产党的推动使它一直出现在公众的视野里。不过,正如怀特指出的,摩尔根是资产阶级革命,而不是共产主义革命的产儿。正如本书最后几页所清楚表明的那样,他从未怀疑他所了解的美国社会制度是社会组织的精华所在。

Marx could not have afforded to be ignorant of Morgan, and was hence “influenced” by him. Marx “needed” Morgan in order to link sociopolitical phenomena to his concepts of evolution by revolution in modes of production. Morgan’s “stages” of human progress were suited to Marx’s needs, as Bachofen’s, for example, were not.

马克思不可能不注意到摩尔根,从而受到他的“影响”。马克思为了将社会政治现象与他的生产方式靠革命才能逐步前进的观念联系到一起,他是“需要”摩尔根的。摩尔根将人类进步分为不同“时期”的理论,恰恰迎合了马克思的需要,而其他人,例如“巴霍芬”的理论,与马克思的需要如枘凿之不相入。

For Morgan himself, however, the stages at the basis of his theory had an utterly different purpose. Morgan’s task was to organize some of the vast bulk of data about exotic societies that had come pouring in during the decades before he worked, and to add system and sense to further collection. Geology, paleontology, biology, and ethnology had all developed, and the quantity of data about foreign parts that was contained in works by travelers and missionaries was truly mountainous. The new vistas of the tremendous sweep of time and the panorama of geographical and human variety could not be accommodated from the old viewpoints. In fact, old categories had to crumble—the nineteenth century was ripe for a new world view—and genetic explanation was in the air.

然而,对于摩尔根本人来说,作为他的理论基础的“时期”理论,实具有完全不同的意义。在他工作的的前几十年,大量有关外族社会的资料涌现,摩尔根的人物就是把其中一部分加以组织,并使进一步收集的材料系统化和具有意义。地质学、古生物学、生物学和民族学都已经发展起来,旅行者和传教士们的撰述中,关于异乡的资料数量之多堆积如山。旧的观点已不能圆满解释在悠久岁月中演变来的新的图景,以及地理的和人类的多样性。事实上,旧的范畴必将会瓦解—一个新的世界观在十九世纪已经成熟—遗传学的解释已在空中盘旋。

Morgan probably never knew that his work was an important element in the foundation for that new world view. In fact, it is doubtful that he was aware that the world view was changing. Leslie White has emphasized that Morgan clung to the world view of early-nineteenth-century Protestant Christianity, for all that he personally never capitulated to its demands for individual salvation.

摩尔根可能从来没想到自己的著作将会成为新世界观奠定基础的的重要因素。事实上,他是否觉察世界观正在改变是存在争议的。莱斯利·怀特强调摩尔根坚守十九世纪初基督教新教的世界观,尽管如此,他个人从未屈服于它对个人救赎的要求。

The problem that Morgan erected his stages to solve was a very much smaller one: he was interested in the American Indians, where they had come from, how they had got where they were, and in the similarities of their social organization to that of classical antiquity. Morgan was first and foremost an ethnographer. He even fell into most of the traps set for ethnographers: he raised general theories on the basis of those more specialized and limited theories he needed to understand “his people,” the Iroquois. He managed to a degree rare in his day to get beyond mere primary ethnocentrism—that arising from his mother culture—but he was thereafter soon entrapped again in Iroquois culture, the first he came to understand intellectually. Morgan gathered most of his own data from the field and from a gigantic correspondence (he was among the first to use the method of questionnaires aimed at “scientific experts” rather than only informants).

摩尔根提出的文化发展阶段所要解决的问题,其实是个小问题。他曾对每周印第安人颇感兴趣:他们来自哪里?他们又是如何到达当时所在地方的?以及他们的社会组织与古典古代社会组织的相似之处?摩尔根首先是一个民族志学家。他甚至落入了民族志学家经常落入的绝大多数圈套:他需要理解“他的民族”即易洛魁人,他首先提出一些专门化并且具有局限性的理论,然后以此为基础进而提出一些概括性理论。他在某种程度上成功地超越了最初的民族中心主义,这在他的时代是非常罕见的——这种民族中心主义源于他的母亲文化——但此后,他很快又陷入了易洛魁文化的泥潭,这是他第一次在思想上理解易洛魁文化。摩尔根自己的大部分数据都是通过实地考察和大量通信收集的(他是最早使用针对 "科学专家 "而不仅仅是信息提供者的问卷调查方法的人之一)。

Morgan’s influence, in short, extended beyond his problem and his contribution to social science; he became one of the creators of a new world view, which came to be called “cultural evolution” or “social Darwinism.” Creators of new world views in one age seem invariably to become scapegoats in the succeeding age. Morgan was, then, rejected beyond his measure as he had been accepted beyond it.

总之,摩尔根的影响超越了他所提出的问题和他对社会科学的贡献;他成为新世界观(即后来称为“文化进化论”或“社会达尔文主义”)的缔造者之一。一个时代的新世界观创造者似乎总是成为下一个时代的替罪羊。后来,摩尔根受到了过分的摈弃,正如他此前受到过过分的袒护一样。

Just as the writers of one age, who are taken up for their fifth-column effect as much as for their scientific contributions, become the scapegoats of the next age, so the scapegoats of one age are likely to become the bellwethers of the next, Lowie, Boas, Radcliffe-Brown, and many others in the early twentieth century either damned Morgan with faint praise, ignored him, or attacked him scurrilously. Leslie White, almost alone, began the revival that is today generally recognized in the profession.

正如一个时代的作家因其第五纵队效应和科学贡献而成为下一个时代的替罪羊一样,一个时代的替罪羊也有可能成为下一个时代的风向标。20 世纪初,洛维、博厄斯、拉德克利夫-布朗和其他许多人要么对摩根褒贬不一,要么对他视而不见,要么对他大肆攻击。莱斯利-怀特几乎是孤军奋战,开始了今天业界普遍认可的复兴。

Morgan, himself, remained little read in the profession for some decades. He will come as a considerable surprise to those who read him afresh, divorced from both the exaggerated charges made by his detractors and the exaggerated claims of latter-day bandwagoneers.

几十年来,摩尔根本人在业界一直鲜有人问津。脱离了诋毁者的夸大指控和后世追随者的夸大其词,重新阅读摩尔根的人一定会对他大吃一惊。

Morgan turns out to be, first of all, a social anthropologist, in that he begins with social relationships and their structures rather than with culture traits and their clustering.

摩尔根首先是一位社会人类学家,他从社会关系及其结构入手,而不是从文化特征及其聚类入手。

Morgan, read in terms of modern anthropological categories, is as much a functionalist as an evolutionist. He held a fully mature theory of the needs of social groups and human beings and an idea (though he did not use the words) of culture as the device by which such needs are met. He fully realized the interconnectedness of all the institutions in any cultural field. Morgan the ethnographer called for detailed studies of specific societies (of the sort that he himself did of the Iroquois). His words could be easily attributable to the early Boas, middle Mead, or mature Evans-Pritchard.

从现代人类学的角度来看,摩尔根既是功能主义者,也是进化论者。他对社会群体和人类的需求有一套完全成熟的理论,并认为(尽管他没有使用这个词)文化是满足这些需求的工具。他充分认识到任何文化领域的所有机构都是相互关联的。摩尔根作为民族志家,要求对特定社会进行详细研究(他本人就对易洛魁人进行过此类研究)。他的话很容易让人联想到早期的博厄斯、中期的米德或成熟的埃文斯-普里查德。

Morgan’s work in anthropology is a structured oeuvre—unlike that of Tylor or Boas, who were both men of less tidy minds. Therefore, evaluating any piece of the work demands locating it in the developing structure. The structure is in fact explicit—and is a major factor leading to misrepresentation of Morgan’s full position. Morgan summarized and repeated his position at the beginning of every book. Too often his critics have given more weight to his summaries than to his original statements. Leslie White (op. cit., p. xxxvii) has pointed out that by the time Ancient Society was written Morgan believed that the theories he had set forth in his Systems of Consanguinity were “established with a certainty approaching the absolute.” White’s statement can be generalized and put another way. As Morgan reduced the length of these summaries, he also threw to the winds the caution with which his ideas were originally put forward. Each précis, therefore, shows its author’s strengths and weaknesses in a particular perspective. Read in context, it is the perspective that Morgan had of his past work as he leaped into his next work, But read out of context, such passages from Houses and House-Life, as the following, seem merely dogmatic:

Throughout aboriginal America the gens took its name from some animal or inanimate object and never from a person. (p. 8.)

. . . the beginning of civilization, as that term is properly understood. (p. 4.)

There was no possible way of becoming connected on equal terms with a confederacy except through membership in a gens and a tribe and a common speech. (p. 25.)

摩尔根的人类学作品是一部结构严谨的作品集。与泰勒或鲍亚士的著作不同,他们的思想都不够如此细致因此,评价他的任何作品都需要将其置于发展中的结构中加以衡量。这个结构本来是清晰明确的—这也是导致摩根的全部立场被歪曲的一个主要因素。摩尔根在每本书的开头都总结并重复了他的立场。批评他的人往往更看重他的总结,而不是他的原话。莱斯利·怀特(见注释①所引的《导言》,第 xxxvii 页)指出,摩尔根在撰写《古代社会》一书时已经相信,他在《人类家庭的亲属制度》中提出的理论已经 "以近乎绝对的确定性确立"。怀特的说法可以概括为另一种说法。摩尔根在缩短这些摘要篇幅的同时,也将最初提出观点时的谨慎态度抛到了九霄云外。因此,每篇摘要都从一个特定的角度展示了作者的长处和短处。如果联系上下文来读,就能知道那是摩尔根在进而写新的著作时,对于他的旧的著作的看法。但如果断章取义,那么。如下面从《美洲土著的房屋和家庭生活》中摘来的几句话,就显得太武断了:

在整个美洲原住民中,所有氏族的名称取自某种动物或无生命的物体,而从不取自某个人。(p. 8.)

. . .文明的开端,就我们正确了解的文明一词的本义而言。(p. 4.)

要想在平等的条件下与部落建立联系,除了加入宗族、部落和共同语言之外,别无他法。(p. 25.)

Morgan’s summaries are, however, also sources of strength, making it possible to see his entire development from ethnographer to comparative social anthropologist. After his basic ethnography of the Iroquois,2 he proceeded to a comparative study of kinship systems in order to validate and set into perspective some of his discoveries.3 That study led him to a method and to a subject matter—social organization—with which he could attempt to set all ethnographic information into a single matrix.4 His last book, the present one, makes as its special point a correlation between architecture and social structure.

然而,摩尔根的总结也是力量的源泉,使我们有可能看到他从民族学家到比较社会人类学家的整个发展历程。在对易洛魁人进行了基本的民族志研究之后,他开始对亲属制度进行比较研究,以验证和阐明他的一些发现。这项研究使他找到了一种方法和一个主题—社会组织—他可以尝试用这种方法和主题将所有的民族志信息归纳成一个单一的矩阵。他的最后一本书,也就是这本书,特别强调了建筑与社会结构之间的关联。

Any evaluation of Morgan’s books must therefore be done in two stages: first, by making a critique of the minutiae that have been corrected or affirmed by the forward march of the discipline, and second, by determining the viability of the large-scale ideas that dominate the entire oeuvre.

因此,对摩尔根著作的任何评价都必须分两个方面进行:首先,对因学科发展而得到纠正或肯定的细枝末节进行批判性看待;其次,确定主导整个作品的主要思想的活力。

Morgan’s last book is still fascinating and instructive today. Although it can no longer be wholly accepted, no book of similar scope has replaced it. Indeed, its theoretical point is only today beginning to be taken up by the specialist subject of proxemics, which is Edward Hall’s word for the study of the relationship between social structures and space, particularly buildings and their placement, transportation modes and their demands on human beings. Therefore, this book, like all anthropological classics, must be read with an informed view of what the problem and the frame of reference were.

摩尔根的最后一本书至今仍引人入胜,具有指导意义。尽管它已不再被完全接受,但没有任何一本类似的书可以取代它。诚然,它的理论今天才开始被社会建筑学这一专门学科所接受。社会建筑学是爱德华·霍尔创造的名词,用以表示对于社会结构和空间(特别是建筑物与其位置、运输方式及其对人类的要求)之间关系的研究。因此,在读这本书时,与读其他人类学经典著作一样,必须清楚地知道问题是什么,观点和理论是什么以及他所在参照系是什么。

Morgan’s problem in this book is a basic one: what does domestic architecture show anthropologists— either ethnologists or archaeologists—about social organization, and how does social organization combine with a system of production technology and an ecological adjustment to influence domestic and public architecture.

摩尔根在这本书中所谈的是一个基本问题:家庭建筑向人类学者——无论是民族学者还是考古学者——在社会组织方面显示了什么,社会组织又如何与生产技术体系和生态学的调整相结合,从而影响了家庭建筑和公共建筑?

Morgan’s method of procedure can only be called “functional-evolutionary,” a term that will be discussed below.

摩尔根的研究方法只能被称为 "功能—进化论",下文将对这个名词进行讨论。

The first chapter and much of the next three are made up of Morgan’s condensation of his position. The Iroquois data have now become the model against which Morgan judges all other ethnographic data. The arguments of Systems of Consanguinity and Ancient Society are set forth with the sanctity of established fact. Houses and House-Life was to have formed a fifth section of Ancient Society, but it was omitted because of the already inordinate length of that manuscript. Morgan printed some of it as articles, and then later reworked it and added introductory summaries.

第一章和后面三章的大部分内容都是摩根对自己立场的浓缩。易洛魁人的数据现已成为摩尔根评判所有其他民族志数据的范本。《亲属制度》和《古代社会》的论据是根据公认的事实提出的。《房屋和家庭生活》原打算作为《古代社会》的第五编,但由于篇幅太长删掉了。摩根将其中的一些内容写成几篇论文发表,后来又进行了修改,并增加了绪论性概要。

A weak point in this book is Chapter X, which is almost a reprint of one of the published articles.Morgan himself said that this should have been rewritten to bring it into line with Bandelier’s new material. Chapter X is also marred by a sarcasm toward his sources, authorities, and adversaries which is rare in Morgan. Not only could he have improved it by rewriting with better material (if, indeed, the Bandelier material was better—a moot point), but he could have made it very much more effective by making it more even-tempered.

本书的一个薄弱环节是第十章,它几乎是已发表文章的翻版。摩尔根自己也说过,这本应该重写,以便与班德利埃的新材料保持一致。摩尔根对第十章所引用的资料来源和对官方材料所持的讥讽态度,表现出他在其他著作中少见的敌对态度,因而有所逊色。他本当利用较好的材料改写这一章(如果班德利埃的素材确实更好的话—不过这是一个争论未决的问题),而且如果他把这一章写的心平气和一些,应当是可以给人更为深刻的印象的。

There are a few other emendations that should be made in this book—none of them seriously affect the main argument, but some of them should nevertheless be noted before we proceed to the much more significant insights and analyses that the book also contains. Morgan misinterpreted the social structure of the Aztecs and the Maya: his theory about unilineal descent groups and the position such groups occupied in his evolutionary stages, combined with the poor quality of the data on social organization left by the Spanish chroniclers, led Morgan to see descent groups where in fact there were none.

本书还应该做一些其他修改——这些问题都不会严重影响主要论点,但在我们开始讨论该书所包含的更为重要的见解和分析之前,还是应该指出其中的一些问题。摩尔根曲解了阿兹特克人和玛雅人的社会结构:因为他的单系继嗣群体的理论以及这些群体在他的进化阶段中所处的地位,再加上西班牙编年史家留下的社会组织数据质量不高,导致摩尔根看到了实际上并不存在的血统群体。

Morgan was also wrong about the Mound Builders of the Ohio and Mississippi valleys. It is an astounding fact that only since about 1960—almost a hundred years after Morgan wrote—has there been any adequate excavation of these sites. Morgan suggested that these mounds were house sites. Present-day opinion is that they were mortuary mounds. There were structures on them, but it is unlikely that they were houses; there were no middens, and evidence of row after row of houses has been found on the regular ground surface, nearby but separated from the mounds. The largest of these mounds to be excavated to date is the Cahokia site near St. Louis, where there are about twenty large, truncated mounds, with traces of some 385 houses in the fields adjacent.Therefore, those parts of pages 228–44 of this book that describe the mounds as house sites, and the ingenious “restoration” that Morgan made in Figures 47 and 48 of a “High Bank Pueblo,” are brilliant—though, unfortunately, inaccurate—guesses; they nevertheless had greater verisimilitude than any other explanations current at the time, or for decades afterward.

摩尔根对俄亥俄河和密西西比河流域的土墩建造者的看法也是错误的。一个令人震惊的事实是,自从 1960 年前后——几乎摩尔根写书后一百年——才对那些遗址进行了充分的挖掘。摩尔根认为这些土墩是房屋遗址。目前的观点认为它们是墓冢。在这些土墩上有建筑,但不太可能是房屋;没有冢,和在附近的地面上发现了一排又一排房屋的证据,但这些房屋与土墩是分开的。圣路易斯附近的卡霍基亚遗址是迄今为止发掘出的最大的土墩,那里有大约 20 个被截断的大土墩,附近的田地里有大约 385 座房屋的痕迹。因此,本书第 228-44 页将土墩描述为房屋遗址的部分,以及摩根在图 47 和图 48 中对 "高岸普韦布洛 "的巧妙 "复原",都是精彩的猜测——尽管不幸的是,这些猜测并不准确;但它们比当时或之后几十年的任何其他解释都更加真实可信。

Two terms in Houses and House-Life call for special comment: land tenure, and what Morgan called “communism in living.”

《房屋和家庭生活》中有两个术语需要特别加以说明:土地使用权和摩尔根所说的 "共产主义生活"。

“Communism in living” meant to Morgan something quite different from what it means today, or indeed from what it meant to nineteenth-century “communists.” To express something like Morgan’s idea today, we would rather uncomfortably use the word “communalism.” What is implied is that some sort of cohesive local community, larger than the nuclear family, is the basic unit of consumption and possibly also of production. Robert Owen’s communities come far closer than do collective farms or even kibbutzim to what Morgan was describing.

摩尔根所说的"共产主义生活 "和今天的意义大相径庭,甚至与十九世纪 "共产主义者 "的意义也大相径庭。在现代语境中我们想要表达摩尔根的观念,我们不太可能用“公社制社会结构”来表达,它的含义是,某种大于核心家庭的、紧密结合在一起的地方社区,既是消费的基本单位,也可能是生产的基本单位。罗伯特·欧文描述的社区,比集体农场,甚至比“基布津姆”(以色列人的集体农场或聚—译注)更为接近摩尔根所描述的社区。

Moreover, Morgan looked back to a period of communism, not forward. To him, the distribution of labor in the nineteenth-century monogamous household and in the new industrial system had far outdated what he called “communism in living.” Morgan’s terminological difficulties reflect a lack that we still feel: we need, and so far as I am aware do not have, a good comparative study of domestic groups, domestic economy, sexual and other division of domestic labor, and what general aspects of society do in fact seem to be co-ordinated with various types of domestic unit (and, to utilize Fortes’ insights,with various event sequences that mark domestic units in different societies of the world).

此外,摩尔根还回顾了共产主义时期,而不是向前看。在他看来,十九世纪一夫一妻制家庭和新工业体系中的劳动分配远远超过了他所说的 "生活中的共产主义"。摩尔根在术语上的困难使我们现在仍能感受到一种缺陷:我们需要(对家庭群体、家庭经济、家庭劳动的性分工和其他分工,以及社会的哪些总体方面实际上似乎与各种类型的家庭单位(以及利用福特斯的见解,与世界不同社会中标志着家庭单位的各种事件序列)相协调进行良好的比较研究,而就我所知,我们还没有这样的研究。

The land-tenure problem is not so simple—even now. Just as domestic groups have been inadequately analyzed comparatively, either by Morgan or by his successors, so have larger-scale local groups and the settlement patterns to which they have given rise. A difficulty lies in the assumption that settlement patterns are to be studied primarily in terms of “property,” “ownership,” and, indeed, “land tenure.” Here is another example of the kind of ethnocentrism that tries to turn the terminology of a specialized Western institution into a terminology suitable for cross-cultural comparison. As usual, much of the obscurity results from the shadow that the Western institution casts.

“土地保有权”不是一个简单的问题——即使现在也不是。无论是摩尔根还是他的继承者,都没有对家庭群体进行过充分的比较分析,也没有对从家庭群体中产生的范围较大的地域群和居住模式进行过充分的比较分析。困难在于人们认为居住模式应当首先根据“财产”、“所有权”、以及“土地保有权”来加以研究。这又是一个民族中心主义的例子,它试图把西方专门机构的术语变成适合跨文化比较的术语。与往常一样,许多模糊不清的地方都是由西方机构投下的阴影造成的。

“Land tenure” and other aspects of human settlement patterns supply a way of looking at territoriality in human beings. Even those animals that do not exhibit aggression in their territorial arrangements (and human beings are among those that do) must place themselves in terrestrial space. That placement is one of the important reflections—indeed, causes—of just what social arrangements are in fact made. Euro-American society has, for the past several centuries, maintained its territorial juxtaposition by means of contract (including treaties), with legal machinery of enforcement. The term “land tenure” is a carry-over from feudal days. Yet history has seen a change in the legal background, from the organizing principle of infeudation to the organizing principle of contract. In the West, a local community nowadays results from contractual sale and rental of land as living sites and as a factor of production. The terms for connecting man with his place in the sun are legal terms.

“土地保有权”和人类定居模式的其他方面为我们提供了一种审视人类领地性的方法。即使是那些在领地安排上不表现出攻击性的动物(人类就是其中之一),也必须将自己置于陆地空间中。这种布局是社会安排的重要体现之一,实际上也是其原因。在过去的几个世纪里,欧美社会一直通过契约(包括条约在内)和法律执行机制来维持其领土并置。“土地保有权 "一词是从封建时代延续下来的。然而,历史见证了法律背景的变化,从封建的组织原则到契约的组织原则。在西方,如今的地方社区产生于作为生活场所和生产要素的土地的合同买卖和租赁。将人与他所处的为众人所知的位置相联系的契约条款,就是合法的条款。

Morgan too saw territoriality in the limiting terms of his own culture and his own profession:

There is not the slightest probability that any Indian, whether Iroquois, Mexican, or Peruvian, owned a foot of land that he could call his own, with power to sell and convey the same in fee simple to whomsoever he pleased. (p. 98.)

摩尔根也从自己的文化和职业局限性的角度来看待地域性:

任何印第安人,不管是易洛魁人、墨西哥人还是秘鲁人,都不可能拥有一英尺属于自己的土地,并有权将其出售或转让给自己指定的继承人。(p. 98.)

Of course there is not. But Morgan’s explanation in terms of communal ownership is not the only explanation— it is merely the one that made it necessary for him to do the least adjustment. A better way of looking at the situation is to ask what the organizational basis of communities may be, and how these communities extend themselves on the surface of the earth, and how they go about exploiting that surface for their daily needs. What Morgan did not realize is that land tenure as he knew it would have destroyed—ultimately did destroy—the very kinship basis of the extended family household. To view the extended family as a corporation aggregate that “owns” the “land” is—to use a literary metaphor—a mere substitution of nouns rather than accurate translation. Better, the extended family lives in a space that is determined by social relationships— relationships among its own members, and between it and other similar groups. That space is exploited and protected. The notion of legal “rights” in the form of a “fee” was alien precisely because when the community (whatever it may have been) left this piece of land, and no longer exploited it, the “rights” lapsed. Morgan copes with this situation in terms of a generalized idea of rights of use.

当然没有。但摩尔根从公有制角度的解释,并不是唯一的解释——它只不过是可以使他做出最少修正的解释而已。审视这种情况的一个更好的方法是,询问社区的组织基础可能是什么,这些社区如何在地球表面扩展自己,以及它们如何利用所选的地方来满足自己的日常需要。摩尔根没有意识到的是,他所知道的土地保有权会破坏——最终确实破坏了——大家庭的亲属关系基础。将大家庭视为 "拥有""土地 "的公共集合体,用文学上的比喻来说,只是名词的替换,而不是准确的翻译。较好的说法是,大家庭生活的空间是由社会关系决定的——家庭成员之间的关系,以及与其他类似群体之间的关系。这一空间得到了开发和保护。以 "祖传土地 "为形式的合法 "权利 ",这个概念是不恰当的,正是因为当社区(不管是什么社区)离开这片土地,不再开发利用时,"权利 "就失效了。摩尔根是以使用权的一般概念来应对这种情况的。

In short, Morgan failed (as we all do) whenever his model for explanation ill fitted his data. One should always ask: (1) What is the source of my model? Then one can proceed to ask: (2) Is it flexible and inclusive enough, so that I am not destroying another folk model by using my model, whatever its source?

简而言之,当摩根的解释模型与数据不匹配时,他就失败了(就像我们一样)。我们应该经常问:(1) 我的模型的来源是什么?然后进一步问:(2) 它是否足够灵活和具有包容性,以便我在使用我的模型时不会破坏另一个民间模型,无论其来源如何?

Morgan’s Lasting Contributions

Two of the problems to which Morgan gave keenest attention are still at the anthropological frontier: evolution and proxemics. Morgan wrote before cultural evolution or even social Darwinism became dogma. Although most of the evolutionary theorists who came after him. built on his work directly, nevertheless it is anachronistic to speak of him as merely an evolutionist. It would be just as anachronistic to say that Morgan was a functionalist, but even the most cursory reading of his books today will reveal principles that since his time have come to be called functionalist. Morgan antedated the distinction, and today we would have to say that funtionalist theory is embedded in his evolutionism, that evolutionary theory is embedded even in his ethnography. The two are not distinguished in Morgan, and therefore he gives us many important clues to the way in which the two fit together.

摩尔根最为关注的两个问题仍处于人类学的前沿领域:进化论和社会建筑学。摩尔根写这篇文章的时候,文化进化论甚至社会达尔文主义还没有成为教条。尽管在他之后出现的大多数进化理论家都直接以他的研究成果为基础,但把他仅仅说成是进化论者是不合时宜的。如果说摩尔根是功能主义者,那也是不合时宜的,但即使是今天最粗略地阅读他的著作,也会发现从他那个时代起,他的原则就被称为功能主义。今天,我们不得不说,他的进化论中蕴含着功能主义理论,甚至他的民族志学中也蕴含着进化论理论。摩尔根并没有将这两者区分开来,但他为我们提供了许多重要线索,让我们了解这两者是如何结合在一起的。

Two interlinked assumptions underlie functionalist theory: (1) that human institutions, and therefore culture, fulfil the needs of human creatures, and ipso facto satisfy the requisites of social life; (2) that within a single society or social field human institutions are perceptually and materially interconnected, and therefore a change inone is likely to bring about a change in the other.

功能主义理论有两个相互关联的假设:(1) 人类的制度,还有文化,满足了人类的需要,也当然满足了社会生活的要求;(2) 在一个单一的社会或社会领域中,人类诸制度在观念和物质上是相互关联的,因此一个的变化很可能会带来另一个的变化。

Morgan assumed both these ideas and added a third: institutions, in the course of satisfying human needs and social requisites, lead people to more efficient or highly prized means of satisfying needs; in the process of so doing, these institutions may create a new, derived set of demands that they themselves can no longer fulfil.

摩尔根假定了这两种观点,并补充了第三种观点:制度在满足人类需求和社会要求的过程中,会引导人们采用更有效或更珍贵的方式来满足需求;在此过程中,这些制度可能会创造出一系列新的、衍生的需求,而这些需求本身已无法满足。

Thus, in satisfying needs, institutions create new needs; in the search for fulment, social change occurs; once change occurs in one institution, concomitant change occurs in some others; once these changes have occurred, simplifying solutions may be found that make reversal impossible because it would be complicating rather than simplifying and hence more trouble for less reward.

也就是说,制度一方面满足需要,一方面又创造新的需要;在寻求满足的过程中,社会发生了变革;一旦一个制度发生变革,其他一些制度也会随之发生变革;这些变革一旦发生,就可能找到简化的解决方案,并且使逆转成为不可能发生的事情,因为这将使问题复杂化而不是简单化,从而增加麻烦,减少回报。

In such a scheme, a functionalist approach is basic to evolutionary theory, and functionalism without an evolutionary theory stops short of full explanation—each type may answer limited questions and different questions, but the rapprochement is vital to still other questions.

在这种结构中,功能主义的探讨是进化论理论的基础,而没有进化论理论的功能主义是做不出完整的解释的—功能主义和进化论各自都能回答有限的问题和不同的问题,而需要回答另一些问题,两者的结合是必不可少的。

Morgan made all these points with great clarity. The first principle of functionalism cannot be better stated than in the sentence: “Every institution of mankind which attained permanence will be found linked with a perpetual want.” (Ancient Society, p. 98.) The second point of functionalism—the interconnectedness of institutions and culture traits—is illustrated by Morgan’s assumption of a relationship between family structure and kinship terminology, or that between family interaction and domestic architecture. The third point—that of functional evolution—is well illustrated in such statements as:

The city brought with it new demands in the art of government by creating a changed condition of society. (Ancient Society, p. 264.)

After an immensely protracted duration . . . the gentile organization finally surrendered its existence . . . to the demands of civilization. It had held exclusive possession of society through these several ethnical periods, and until it had won by experience all the elements of civilization, which it then proved unable to manage. (Ancient Society, p. 350.)

摩尔根非常清晰地阐述了所有这些观点。下面这句话把功能主义的第一个原则表现得极为深刻:“人类制度中凡是能维持长久的都与一种永恒的需要有关。”(《古代社会》,第98页)对于功能主义的第二点--制度与文化特征之间的相互联系--体现在摩尔根对家庭结构与亲属称谓制度之间关系的假设,或家庭互动与家庭建筑之间关系的假设。第三点——功能性进化——在下面这样的陈述中得到了很好的说明:

这城市改变了社会状况,对政治艺术提出了新的要求。(《古代社会》,第 264 页)。

在经历了漫长的岁月之后......氏族组织最终向文明的需求交出了自己的存在......氏族组织在人类文化的这几个阶段中曾经一直垄断者社会,直到它通过经验赢得了文明的所有要素,但,于此它已经表现出没有能力来处理这些因素了。(《古代社会》,第 350 页)。

Within the present book, functional-evolutionary statements like the following occur:

As a key to the interpretation of this architecture, two principles, the practice of hospitality and the practice of communism in living, have been employed. (p. 310.)

It was the weakness of the family, its inability to face alone the struggle of life, which led to the construction of joint-tenement houses throughout North and South America by the Indian tribes; and it was the gentile organization which led them to fill these houses, on the principle of kin, with related families. (p. 268.)

作为诠释这一建筑的关键,我们采用了两个原则,即好客的风尚和共产主义生活实践。(p. 310.)

家庭的弱点是它不能单独应付生活的斗争,所以北美和南美的印第安部落都普遍地建造群居大房屋;氏族组织按照亲属原则则使这些大房屋住满了有亲属关系地家庭(P.268)

The examples could be multiplied.

Indeed, one of Morgan’s greatest evolutionary errors comes from too rigid a reading of functional requirements. Band organization is a limiting factor—bands can organize people only until population density and technology reach a certain level of complexity. After that, it is not adequate. The band must separate into two bands, or a new and simplifying social mechanism is needed. Such a point is not in question. Morgan, however, assumed that the unilineal descent group was the next step in all instances. We have already noted that many other types of organization can fulfil the same needs and therefore succeed the band in an evolutionary sense. Morgan had the right vision, but he narrowed it too soon.

事实上,摩尔根最大的进化错误之一就是对功能需求的解读过于僵化。群组织使一个起限制作用的因素——只有在人口密度和技术还没有达到一定复杂的水平之前,群才能把人们组织起来。在此之后,它就无能为力了。一个群必须分离成两个群,或者需要一个新的、简化的社会机制。这一点毋庸置疑。然而,摩尔根认为单系继嗣群体在所有情况下都是继发的。我们已经注意到,许多其他类型的组织可以满足同样的需求,因此从进化的意义来说,它们是继群之后出现的。摩尔根有正确的愿景,但他过早地缩小了它的范围。

Today we can see that it is the local groups—not the families—that can be placed on an evolutionary ladder. Seeing that point might have allowed Morgan to avoid what was probably his most telling misstep: dependence on a theory of survivals in general and of kinship terminologies as survivals in particular. Today, most anthropologists accept the idea that local groups fit onto an evolutionary scale, and that some types of local groups are based on kinship principles but others are not. It is very doubtful, however, that known extant types of family structure form an evolutionary progression, although it is easier to move from each to some than to some others. Morgan, to achieve his evolutionary stages, had to make a division between the family based on monogamous marriage and all the other types of known family forms, and then to postulate and arrange in moral sequence the earlier stages. Such stage building made an unwarranted assumption: that some forms of family organization are more complex than others. It would seem today that monogamous family forms can move to some polygamous form (what Morgan called the “syndyasmian family”) as well as from it to monogamy. Morgan’s earlier stages are either errors in reporting, reconstructions from inadequate facts, or not present today in human society. Today, however, we are returning to the idea that early forms of social organization among the early forms of man that were to become homo sapiens resembled that of the baboon troop. In terms of group morphology then, Morgan’s intuition was close; his reconstruction of process, via kinship terminology, is no longer adequate.

今天,我们可以看到,可以被置于进化的阶梯上,是地域群,而不是家庭。明白了这一点,摩尔根可能就能避免他最明显的失误:依赖于一般的遗存理论,特别是作为遗存的现象的亲属称谓制的理论。如今,大多数人类学家都接受这样的观点,即地域群符合进化阶梯的思想,某些类型的地域群以亲属关系原则为基础,而另一些则不然。然而,已知的现存的家庭结构诸形式能否形成一个进化的系列,这一点非常值得怀疑。摩尔根为了实现他的进化阶段,不得不将基于一夫一妻制婚姻的家庭与所有其他类型的已知家庭形式区分开来,然后按照道德出现的先后顺序假设和安排早期阶段。这种阶段论做出了一个毫无根据的假设:某些家庭组织形式比其他家庭更复杂。如今看来,一夫一妻制的家庭形式可以转变为某种一夫多妻制的家庭形式(摩尔根称之为 "一夫多妻制家庭"),也可以从一夫多妻制家庭转变为一夫一妻制家庭。摩尔根的早期阶段要么是报道错误,要么是根据不充分的事实进行重建,要么是当今人类社会所不存在的。然而,今天我们又回到了这样一种观点,即早期人类(即后来的智人)的早期社会组织形式类似于狒狒群。就群体形态而言,摩尔根的直觉是接近的,但他通过亲属关系术语重建的过程已不再合适。

Another aspect of Morgan’s evolutionary theory also provides some difficulty: stage building is simple only in theory. Today we know that to mark the end of a stage or “condition of civilization,” as Morgan called it, it is necessary that new modes of communication, energy use, or social organization occur which not merely transcend earlier forms but render those earlier forms unusable. Resulting changes are thus irreversible in that they combine efficiency and simplicity to the point that a backward step would be not merely uncomfortable but more difficult of comprehension and achievement than a forward step. Fire making, family organization, domestication of animals, and planting of food crops—all these (and many others) are so simple and so efficient that, even though precise techniques may be lost, the idea is in the minds of men and. will be carried through because the earlier alternative is more difficult. Thus, the great simplifying ideas—cooking, planting, money—are the “mutations” that lead to the “gene loss” of earlier forms.

摩尔根进化论的另一个方面也引起了争论,因为阶段论仅仅在理论上是简单方便的。今天我们知道,要标出一个阶段即摩尔根称之为“文明状况”的终结,必须出现新的通信、能源使用或社会组织模式,它们不仅要超越早期的形式,而且要使早期的形式无法使用。因此,由此产生的变化是不可逆转的,因为它们将效率和简便性结合在一起,以至于后退一步不仅会感到不舒服,而且比前进一步更难理解和实现。生火、组织家庭、驯养动物、种植粮食作物——所有这些(还有许多其他的)都是如此简单和高效,以至于即使精确的技术可能已经失传,但人们的头脑中仍有这种想法,并且会将其付诸实施,因为采用先前的方式更加困难。因此,伟大的简化思想——烹饪、种植、金钱——是导致早期形式 "基因丧失 "的 "突变"。

Today, the evolutionary principles of Morgan lead, almost automatically as it were, into one of the standard practices of twentieth-century sociology—scaling. One of the fundamental scales is the Guttman. It works simply: if a collection of items “scale,” items A, B, and C are always present if item D is present, but A, B, and C may be conjoined without D; moreover, where C is present, A and B are to be found, but A and B may be found without C, and so on. In tabular form, a perfect Guttman scale appears:

+ + + +

+ + + -

+ + - -

+ - - -

- - - -

如今,摩尔根的进化原则几乎自然而然地发展成二十世纪社会学的标准实践之一——等级量表。其中一种基本的量表是古特曼量表。它的工作原理很简单:如果一个项目集合 "量表 "中存在项目 D,则项目 A、B 和 C 总是存在的,但 A、B 和 C 也可能在没有 D 的情况下结合在一起;此外,在存在 C 的情况下,A 和 B 也是存在的,但 A 和 B 也可能在没有 C 的情况下存在,依此类推。以表格的形式出现了一个完美的古特曼量表,如下:

+ + + +

+ + + -

+ + - -

+ - - -

- - - -

Several recent studies have brought the Guttman scale into play in determining questions of social complexity, and ultimately of evolution.

最近的几项研究让古特曼量表在确定社会复杂性问题以及最终的进化问题上发挥了作用。

The only major difficulty that needs to be mentioned here is one that Morgan would have grasped and pointed out immediately: functional equivalents may supplant one another and give the illusion of disjunction in the scaling order. One can avoid this difficulty in two ways: one is to do what Goodenough did and create a “quasi-scale”; the other is to enlarge the category of one of the units in the scale, and so have scales within scales. That is, if item B is replaced by item M, then item B must be called by a larger category name, the former item B relabeled B1 and M renamed B2 . If B1 B2 do not scale, but rather are interchangeable (as I have claimed that all extant family forms seem to be), then the new label for B still fits; if B1 B2 do scale, we have a subordinate type of scale or “quasi-scale” that illuminates the first.

这里唯一需要提及的主要困难,是摩尔根本来会立即抓住并指出的,即:在功能上相等地事务可以相互替代,并在等级次序中产生一个脱节的假象。要避开这个难题有两个办法:一个办法是像古迪纳夫那样,创造一个“准等级”;另一个办法是将等级中的一个单位扩大,使等级中还有等级。那就是说,如果项目 B 被项目 M 取代,那么项目 B 就必须用一个更大的类别名称来称呼,以前的项目 B 被重新命名为 B1,而项目 M 则被重新命名为 B2。如果 B1和 B2 没有标度,而是可以互换(正如我所说的,所有现存的系列形式似乎都可以互换),那么 B 的新标签仍然适用;如果 B1 和B2 有标度,我们就有一种次级量表或‘准量表’来阐明第一个量表。

Morgan’s inadequacies for the mid-twentieth century can be seen if we accept the idea of two scales in evolutionary situations. Morgan set the boundaries of his stages by technological inventions. Some of these technological inventions do not scale: writing, for example, may or may not antedate pottery; the bow and arrow may or may not antedate metallurgy. In every instance, we must go to the data in any specific area, because no evolutionary scaling is possible. Such scaling can, on the other hand, be made in terms of energy use, as White has done, or in terms of local organization. Morgan used cultural inventions for his indicators of stages, then looked for functional and organizational correlates. Had he been more aware of functional equivalents, he would have made more nearly correct stages.

如果我们接受在进化情境中存在两个量表的观点,就可以看出摩尔根在二十世纪中叶的不足之处。摩尔根以技术发明为各个阶段的界限。有些发明创造是无法列入等级中的,例如文字可能早于也可能迟于制陶术,弓箭可能早于也可能迟于冶金术。每个实例,我们都必须根据各个地方的资料,因为在进化论上分等级是不可能。另一方面,也可以像怀特所做的那样,从能源使用的角度或从地方组织的角度来确定这种等级。摩尔根使用文化发明作为阶段指标,然后寻找功能和组织方面的相关因素。如果他对功能等价物有更多的了解,他就会做出更接近正确的阶段划分。

We can now restate Morgan’s evolutionary position in terms of current problems. Families can perform all the necessary functions for the maintenance of the individual and society. They can, however, do it only within a comparatively small compass. Therefore, when they are successful, the compass of the society enlarges; society must break into what Durkheim would have called units in mechanical solidarity, which must remain independent of one another (which means, in this context, without effective social relationships between the independent units) or a new social institution must be added to assume responsibility where the capability of the family ceases. One of the widespread forms to assume this new task was the unilineal descent group—a culturally obvious group because it utilizes kinship solidarity as its means for demanding loyalty. Other types of groups, however, founded on propinquity or contract or the principle of the common weal, will also work.

现在,我们可以从当前的问题出发,重述摩尔根的进化论立场。家庭可以履行维护个人和社会的所有必要职能。然而,它们只能在相对较小的范围内做到这一点。因此,当它们取得成功时,社会的范围就会扩大;社会一定会进入到为杜克海姆所说的机械团结的单元,这些单元必须保持相互独立(在这里,这意味着独立单元之间没有有效的社会关系),或者必须增加一个新的社会机构,在家庭能力不再的地方承担责任。承担这一新任务的普遍形式之一是单系继嗣群体——一种文化上显而易见的群体,因为它利用亲属团结作为要求忠诚的手段。然而,其他类型的团体,如建立在亲缘关系、契约或共同利益原则基础上的团体,也同样可以发挥作用。

Morgan’s primary work on evolution came earlier in his career than did his work on proxemics. His publishing history, however, emphasizes the point disproportionately, because the material that became Houses and House-Life was removed from Ancient Society and so failed to show how unitary the ideas were for Morgan. Morgan’s evolutionary schemes are in terms of families and family types, associated with kinship terminology and with political structure. His work on proxemics concerns the way that local groups and families intercorrelate with settlement patterns and architecture. It is associated with his struggles to interrelate culture traits and social structure. Anthropology has been slow to realize the importance of Morgan’s lead in this field which he, in a very real sense, founded but did not name. Some of the most interesting new work in this field is being done by Edward Hall.

在摩尔根的学术活动中,关于进化论的主要著作比他的社会建筑学方面的著作出现的早。然而,摩尔根的出版史却不相称地强调了这一点,这是因为《房屋与家庭生活》的材料是从《古代社会》中挪过来的,因此无法显示摩尔根的思想的一致性。摩尔根的进化方案以家庭和家庭类型为基础,与亲属称谓制和政治结构相关联。他的关于社会建筑学的著作,讲述地域群和家庭与居住模式和建筑之间相互影响的方式;也表现出他把文化特征和社会结构相连结的努力。人类学迟迟没有意识到摩尔根在这一领域的领先地位的重要性,从真正意义上说,摩尔根创立了这一领域,但却没有为其命名。目前爱德华·霍尔(Edward Hall)在这一领域开展了一些最有趣的新工作。

The contributions of Lewis H. Morgan show more contemporary vitality today than they have for several decades. Indeed, today students (who, from before 1930 almost until 1960 could get along without him) will find it necessary to turn back to Morgan, not merely to learn the history of their subject, but more importantly to avoid what Gunnar Myrdal once called, speaking of Lord Keynes, “unnecessary Anglo-Saxon originality.”

与前几十年相比,路易斯·摩尔根的贡献在今天显示出了更大的活力。事实上,今天的学生(从1930年之前几乎到1960年,没有摩尔根也能过得很好)会发现有必要回头看看摩尔根,这不仅仅是为了学习他们学科的历史,更重要的是为了避免贡纳尔·米达尔在谈到凯恩斯勋爵时所说的 "不必要的盎格鲁·撒克逊独创性"。